| current issue |

| archives |

| submissions |

| about us |

| contact us |

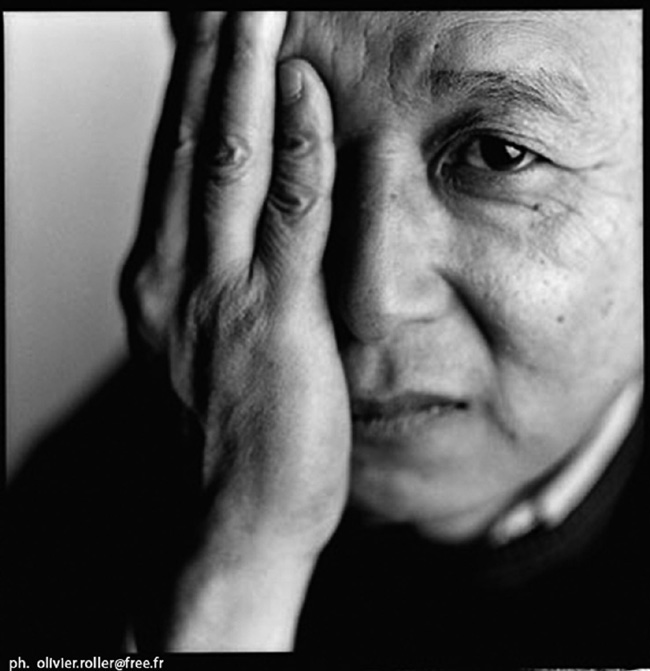

The Case for Literature by Gao Xingjian reviewed by Adair Jones |

At the end of Mao’s disastrous political campaign, thousands of intellectuals and artists were dead, but Gao Xingjian had survived. He returned to Beijing. The older established writers who survived remained wary, writing little, but Gao became part of a cohort of younger writers who grew emboldened with new freedoms and began to test the political climate with brave and brazen new works. After the long period of enforced silence, Gao wrote prolifically, as he would continue to do for the rest of his writing career. Blacklisted In 2000, Gao Xingjian was awarded the world’s highest literary honour, the Nobel Prize for Literature. Writing through the Cultural Revolution This emphasis on the personal nature of writing is what saved him. When he was able to write openly, he wrote openly; when he couldn’t, he wrote secretly. When he was forced to flee, he fled. Gao would not martyr himself to be ‘a writer’. But he would always take the risk of writing—because he wasn’t writing necessarily to be read, he was writing to be himself. This lack of ‘preciousness’ makes that suitcase of burnt manuscripts less tragic and the Nobel Prize all the more fitting. Traditional and Revolutionary Themes His work is characterised by the blending of classical Chinese literature with western literary and philosophical influences. Gao is interested in the psychology of his characters and in the moral ambiguity of their situations, a striking departure from the uses of literature demanded by the Cultural Revolution. Even in his most serious works, however, he writes with simplicity, clarity and a wry humour. These essays are brilliant and thought-provoking, which may at times make them hard going, but for those with the will to persevere and an interest in the mind of a masterful artist, the rewards are many. Some of the finest literature is born of repressive regimes, and Gao’s work is a powerful example. In The Case for Literature, we have a view of a rich imagination and the aesthetic philosophy behind it. But more interestingly, we are given a rare glimpse of a thinker and an artist, and of a man who is keenly aware of the value words have to a life. *** |