| current issue |

| archives |

| submissions |

| about us |

| contact us |

| competition |

Unfinished business: why science still hasn’t vanquished religion by Sandra Hogan |

I am very grateful for my liberal upbringing and education and the ability they give me to question and explore ideas and to live freely. But sometimes I wonder whether, if I had been brought up in a religious home, I might have been less conflicted, less scattered in my responses, more substantial, more whole. My father was the youngest son in a Melbourne family of the kind known in his childhood as a ‘mixed marriage’. His father was Catholic and his mother Protestant. Every second child of the marriage was christened a Protestant and every other child a Catholic. Dad was a Catholic and was sent to a Jesuit school. He went along with the faith for a while although, being a very good child, he had to make things up for confession, which bothered him. After a while, the whole question of religion seemed increasingly unlikely and he stopped believing in it without any difficulty or doubt. He was a humanist who believed in treating people with respect and dignity and he put his beliefs into practice all his life. He died at the age of 80 and, as far as I knew, he was content that his life had been well-lived, that it was over and that there would be nothing else afterwards. My mother’s loss of faith was more painful: a harder, crueller loss. She was raised as an Orthodox Jew in Germany. Her Polish parents had gone to live in Germany to escape the pogroms; Germany in the 1920s was considered a place of liberalism, where Jews could live and work more freely than anywhere else in Europe. It is hard now to believe how hopeful that period was for Jewish people, before the rise of Hitler, how free and flourishing their lives were, how well they generally got on with their Gentile neighbours. By 1938, my 14-year-old mother had been dismissed from the German school she attended. She was forbidden to go swimming or to join clubs. There were days when this beautiful girl was not allowed out on the streets, in case her Jewishness would contaminate others. Once, from her window, she saw Hitler driving by in an armoured car with crowds of Dresden citizens, her neighbours, lining the streets and screaming ‘sieg heil’. That year, after the horror of Kristallnacht, my mother escaped Germany, leaving behind her family, her home, her language and everything she cherished. She was one of the children saved from genocide by the Kindertransport movement, which took children by train to foster homes in Britain. The Kindertransport movement was organised by both Jewish and Quaker groups in England, with support from government. My mother’s life was saved by those gentle and determined people of faith. Six years later, when the war had ended with Hitler’s defeat, my mother hoped to be reunited with her family and restored to the life she had lost. But a distant cousin, who had survived the concentration camps, came to visit her in London and told her that all her family had been killed. It was better not to ask any more questions about it. My mother had kept her faith through all her difficulties, but it ended with that news. ‘If there is a God in heaven, how could he allow this to happen? You realise it’s just not possible,’ she said to me, years later. My mother’s loss of faith was not a matter of temperament. It was a response to the terrible loss of family, home, language, culture and identity. It was associated with the deep anger, shame and tormented grief that every Holocaust survivor is familiar with. In rejecting God, Mum was not merely coming to a rational conclusion, although that was part of it. She was also rejecting, with despair, everything that had previously been good and trustworthy and hopeful in her life.

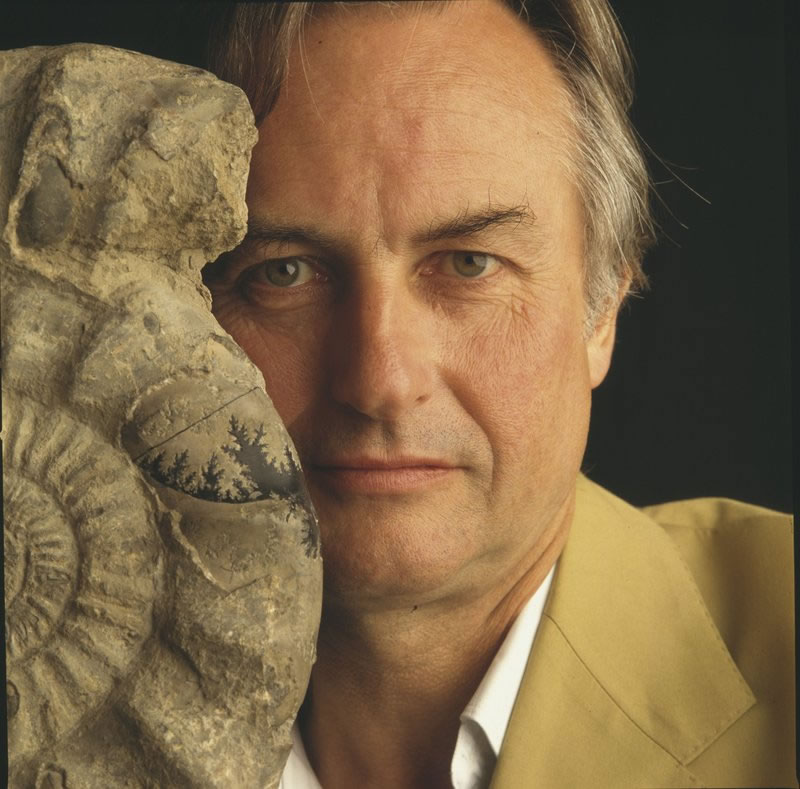

Atheist writer Richard Dawkins, in his book The God Delusion, thanked his parents for taking the view that children should be taught not so much what to think as how to think. ‘If having been fairly and properly exposed to all the scientific evidence, they grow up and decide the Bible is literally true or that the movement of planets rules their lives, that is their privilege. The important point is that it is their privilege to decide what they think and not their parents to impose it by force majeure.’ (Dawkins, 2006:327) I am also the product of such an exemplary upbringing. My father, a kind and gentle man, was a scientist and a rationalist; he described himself as an agnostic but clearly had never struggled with any doubts about the possible existence of a personal god. My mother, whose children were her first concern in all things, was a firm atheist. By common consent, my parents sent my sister and me to the local C of E Sunday school when we were small, so we would understand the culture of the neighbourhood but, hopefully, not catch it. And yet I did catch it, on and off. I have grown up with a yearning for religion, or at least for spirituality. I have dabbled with Methodism, Catholicism, Buddhism, Judaism, the I-Ching, meditation and Tarot cards. I wish on the stars and pray in aeroplanes. These dabblings and yearnings alternate with periods of whole-hearted scepticism and scorn for exactly those things I long for; some of my friends know me as a materialist and an atheist and others as someone with an interest in spirituality. In Somerset Maugham’s great classic, Of Human Bondage, Anglican schoolboy Philip becomes an atheist when he discovers that if he had been raised in South Germany, he would have been a Roman Catholic. After considering the evidence, he decided there was no particular reason why one should believe in God. Suddenly, ‘he could breathe more freely in a lighter air. He was responsible only to himself for the things he did. Freedom! He was his own master at last. From old habit, unconsciously he thanked God that he no longer believed in Him.’ (Maugham, 2000:131). The narrator in Of Human Bondage thought Philip’s complete conversion to atheism was a matter of temperament:

The first time I read The God Delusion, I was excited by it and felt as though I had shed a skin that was too tight. For a few days, I was converted to Dawkins’ rationalism, believing I had found a way to be free of fear and prejudice. Within a week, though, I was embarrassed by my own enthusiasm. I detected something ignoble in my response, so I re-read the book and realised, uncomfortably, that part of my pleasure in the reading had been in the clever and often amusing way Dawkins jeered at the faithful. I had thought Dawkins was like The Chaser, boldly making fun of corrupt institutions and absurd behaviour. And he is; but, while The Chaser focuses its satire on people with power over others, Dawkins also mocks ordinary people, people like me, for our deepest beliefs and hopes. There is no tenderness towards fallible humanity in Dawkins’ writing; he argues against tolerance and support for diversity. I was attracted to his arrogance. I was taking sides with my own scepticism to mock my openness to the world of the unseen and mysterious. My embarrassment led me to the library in search of an approach to religion which would suit my temperament. It would need to satisfy my longing without insulting my intelligence, to honour both mother and father.

Atheist writers like Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, evangelising for the end of religion, have reached the pinnacle of marketing success: their books are on sale at the airport. (Air flights are traditionally a time when even atheists have been known to say a quiet prayer, but clearly modern travellers are made of sterner stuff.) They are getting some competition from defenders of religion. Last time I flew, for example, I bought a copy of Roy Williams’ God Actually: Why God probably exists, Why Jesus was probably divine and Why the ‘rational’ objections to religion are unconvincing, in case it was a bumpy flight. But the atheists seem to be dominating sales, a notable change from previous years when the only books about religion readily available were books with the word ‘happiness’ in the title, preferably ones by the Dalai Lama. There is a tone of urgency in the atheist books. In the preface to The God Delusion, Dawkins says his highest hope is that religious readers who open the book will be atheists when they put it down. He sees religion as a persistent false belief held in the face of contradictory evidence and a danger to the world. Dawkins, Hitchens and other writers known collectively as the New Atheists began publishing in the wake of the September 11 bombings of 2001, when the dangers of fundamentalist religion became starkly evident to the Western world. Dawkins is also driven to protest by the growing power of right-wing Christian groups in the UK and the US seeking—with some success—to introduce creationism into the science curriculum in schools. But Dawkins does not single out religious fundamentalists for attack. Rather, he sees every religion, however mainstream, as fundamentalist. All religions, at heart, have the same basic vice he argues: they teach people, starting from little children, to believe that unquestioned faith is a virtue. ‘As long as we accept the principle that religious faith must be respected simply because it is religious faith, it is hard to hold respect from the faith of Osama bin Laden and the suicide bombers,’ writes Dawkins. ‘The alternative, one so transparent that it should need no urging, is to abandon the principle of automatic respect for religious faith’ (Dawkins, 2006: 306). The new atheists fear a resurgence of religion. They hope to encourage people to stand strongly for atheism or risk falling into the hands of suicide bombers, right-to-lifers, gay-bashers, creationists and other faith Nazis. Yet British philosophy professor, AC Grayling, in an essay called The Death Throes of Religion, interprets contemporary interest in religion differently.

Grayling argues that the prominence of religion in the media makes it seem that religious devotees are everywhere, but less than 10 per cent of the British population attend church, mosque, synagogue or temple every week and this figure is declining.

Grayling belongs to a school of thought reaching back to the intellectual movement of the 18th century known as the Enlightenment, which argued that human reason could be used to combat ignorance, superstition, and tyranny in order to build a better world. Religion was one of the principal targets of Voltaire, Rousseau and other Enlightenment figures. In the 19th century, the war against religion waged by Voltaire and Rousseau was continued by the giants of psychoanalysis, biology and politics: Freud, Darwin and Marx. In a fascinating exploration of Freud’s atheism, A Godless Jew, Peter Gay says Freud liked to say that psychoanalysis had ‘dealt man’s narcissism the most consequential of insults. First Copernicus had attacked that narcissism by demoting man’s abode, the earth, from the centre of the universe; then Darwin had reduced proud man to the status of an animal. Now Freud demonstrated that reason is not master in its own house’ (Gay, 1987:64). Freud saw no possibility for compromise between religion and science, believing that the more knowledge we had, the more people would defect from religion. Like Grayling today, he believed it was inevitable that reason would conquer religious faith. Dawkins’ science descends, via Darwin, from the same Enlightenment tradition as Grayling’s philosophy so, despite his apparently greater atheistic urgency, he still believes religion will disappear if parents and schools stop indoctrinating children with religion from an early age. John Gray, a professor of European thought at the London School of Economics, says that from a Darwinian standpoint the crucial role Dawkins gives to education is puzzling. ‘Human biology has not changed greatly over recorded history and, if religion is hardwired in the species, it is difficult to see how a different kind of education could alter this’ (Gray, 2008). Gray said Dawkins’ belief in the value of education reminded him of ‘the evangelical Christian who assured me that children reared in a chaste environment would grow up without illicit sexual impulses’ (Gray, 2008). Gray also points out that growing international secularism, which seemed to bear out Enlightenment beliefs in the defeat of religion by knowledge, was partly illusory. He says that the mass political movements of the 20th century - communism and Nazism - were ‘vehicles for myths inherited from religion’ (Gray, 2008) so that it was not surprising that religion was reviving now that those movements had collapsed. This comment of Gray’s reminded me of an incident during a visit with my family to Lviv, in the Ukraine. Our guide pointed out a beautiful church. He said that during Soviet rule, the church had been converted into a museum of religion. It included many religious exhibits arranged to show how they had withered away as part of the inevitable progress towards atheism, socialism and true Soviet enlightenment. After the Soviets left, the museum became a church again. It seemed the Soviets, like Dawkins, were deluded as to the withering power of education on religion.

My personal story underlines two faults in Dawkins’ reasoning. One of these is his theory about the Zeitgeist. Dawkins argues that religion is not necessary for morality because morality improves steadily without any connection to religion. Once slavery was acceptable in society, now it is not. Once women were not allowed to vote, now they are ‘Whatever its cause, the manifest phenomenon of Zeitgeist progression is more than enough to undermine the claim that we need God in order to be good, or decide what is good' (Dawkins, 2006: 272). My mother’s story reminds me that this is historical nonsense. Anti-Semitism has existed for thousands of years but in that time and place it had nearly disappeared, until it was revived by Hitler. Marilynne Robinson, author of Gilead, also noted this historical error in her 2006 response to The God Delusion. ‘It is precisely the swiftness with which the Zeitgeist can change that makes it profoundly unworthy of confidence,’ she writes (Robinson, 2006). Robinson believes in religion, politics, philosophy, music and the idea that people have souls, and that they have obligations to their souls and take pleasure in them. She argues for these things in a passionate book of essays called The Death of Adam (Robinson, 2005), which reveals her distrust of the morality of the Zeitgeist in its current expression of consumerism, cynicism and the social Darwinist interpretation of survival of the fittest. The second error in Dawkins’ argument is his belief in the power of a rational education in eliminating religion. Reason, grand as it is, is only one aspect of our education. The influence of unspoken feelings, expressed in silence or in anger, in music or in gesture, is also a fundamental part of our education. What we say and teach can be contradicted powerfully by these feelings. The kind of liberal education prescribed by Dawkins is not enough, in itself, to produce a sceptical outlook. To produce an entirely sceptical population, many of us would somehow have to cut ourselves off from our deepest feelings, desires and sense of what is true.

But this doesn’t address Dawkins’ two main points: that religion is untrue and that it is universally destructive. I needed to explore those issues, starting with the notion of truth. In The God Delusion, Dawkins attacks people’s faith in a superhuman, supernatural intelligence who deliberately designed and created the universe. His targets are Yahweh, God, Allah, Vishnu, Zeus and all the others, though his focus is mostly on the Christian god. He argues that the world came about through gradual evolution and that, although the beginning is still unknown, a god figure is a most improbable theory for the origins of life. Religion, for Dawkins, includes the whole package: all the personal beliefs and also the institutions and dogmas for each faith. My interest in religion is not in the institutions and dogmas. It seems obvious to me, as to Philip in On Human Bondage, that churches, temples, creeds and dogmas of different faiths contradict each other, most notably in the fact that they all claim a monopoly on the truth. Individuals have a religious experience; traditions are developed from that experience to bring people into direct connection with the divine, or at least to remind them of the existence of the divine; finally institutions and creeds are formed to promote and enforce those traditions. An institution is a home or a prison for different people but it is never the truth. Yet religious tradition may provide a concrete, material reminder of an invisible, elusive spiritual truth. Melbourne Jewish scholar, Debbie Masel, describes the way the annual Jewish celebration of Pesach (Passover) embodies an experience people describe as a connection with God. Pesach is a ritual in the form of a family meal where the Biblical story of Exodus is recounted and relived:

Ritual connects people with an individual experience of something we call the divine. If there is truth in religion, it lies in that experience. Exploring the individual experience of divinity seems a more productive place to search for truth than comparing the creeds and institutions that spring from those experiences and live off them. This approach was confirmed for me by a conversation with a friend, Donna, who is a practising Catholic and a regular church attender. She says, ‘I know the Catholic church is corrupt and I don’t like it but that’s not relevant to my faith. There are parts of the creed that I won’t recite because I don’t agree with them. But church reminds me of the things I love and value, which go way beyond the body. If we are just body, what is love? Religion is a candle I need to keep alight. I couldn’t get up in the morning if that small fire went out.’ Even for people who don’t come from the monotheistic tradition of religion, personal experience is the key to their practice. Julie practices Zen Buddhism and a form of moving meditation called Qi Gong. She describes the process of meditation this way: ‘If we can learn to let go of the habitual chattering mind and live in the present moment, in our body, we can experience something beyond words. You can only know it by experience. I don’t theorise about it and I don’t like to talk about spirit because it’s not outside our body. It’s whatever we are this minute. The whole dualistic idea—spirit or body—is very Western. In Asia, everything is one and always changing.’ So the real question for me is whether there is any truth in that individual experience of the divine or whether, as Dawkins argues, it is a delusion. He dismisses the argument from personal experience in five brisk pages. Here is the nub of it:

A hundred years before Dawkins, a doctor, psychologist and philosopher called William James addressed this same question and came up with a different answer. William was brother to the novelist Henry and, in his different field, was just as brilliant. In 1901, he delivered a series of guest lectures on religion at the University of Edinburgh. The Gifford Lectures were compiled in a book called The Varieties of Religious Experience. I am not the first person to fall under their spell as they have been reprinted many times in the last century and translated into Danish, French, German, Italian and Swedish. Arthur Darby Nock, who wrote the 1960 introduction to Varieties said it was ‘the only book about the psychology of religion, in fact the only book about religion … which you could conceivably choose to take to a desert island with you' (James, 1960: 21). James was fascinated by people’s religious experiences and describes them with both tenderness and tolerance. He tips his hat to the Dawkinses of the world by outlining the rationalist or scientific approach, which has no place for vague impressions of something undefinable, and admiring its ‘splendid intellectual tendency’. But he points out:

This, of course, doesn’t prove that personal experience is objectively true, just that logic won’t convince us it is not. James agrees that it is dogmatically impossible to decide about the truth of spiritual experience (as opposed to people seeing pink elephants and thinking they are Napoleon, which can be judged objectively). He goes on to make a helpful comparison between different kinds of reality expressed in scientific and religious thought. The pivot of religious life is the interest of the individual in his private destiny. Science, on the other hand, repudiates the personal point of view; scientific laws are indifferent to human anxieties and fates. The religious mind is impressed by:

Science, of course, sees all that as an anachronism, a left-over from primitive thought.

James concedes the appeal of the impersonality of science but believes it to be shallow because ‘as soon as we deal with private or personal phenomena as such, we deal with realities in the completest sense of the term’ (James, 1960: 476). James’ point is that there are two types of reality: subjective and objective. Objective ideas give us ideal pictures of something whose existence we do not inwardly possess—for example, the information that the world is round—while subjective ideas emerge from our experience. Our personal experience may be less significant than our objective knowledge but it is ‘a full fact’.

James isn’t asking us to jettison scientific and objective reasoning. He simply points out that science can’t disprove the truth of religion (any more than religion can objectively prove its truth). Both are different aspects of reality and he asks us to value our personal reality as well as what we are told to be true.

At this point, it becomes almost futile to examine each of the arguments Dawkins provides to disprove religion (or indeed, any of the theological arguments used to prove its existence). For example, the central chapter in The God Delusion is titled Why There Almost Certainly Is No God. In it, Dawkins argues that a creator God must be more complex than his creation, but this is impossible because if he existed he would be at the wrong end of evolutionary history. To be present in the beginning he must have been unevolved and therefore simple. Marilynne Robinson counters this argument, with more exasperation than James, but using the same principles, by pointing out that evolution is the creature of time and that the scientific ‘big bang’ theory suggests that time and the universe came into being together in a giant cataclysm.

Likewise, when Dawkins points out factual and historical errors in the Bible and criticises ethical behaviour in the Bible, he misses the point for many religious people. I asked Debbie Masel if she believed the Bible was literally true. ‘I don’t know,’ she answered. ‘If I found out there definitely was an Exodus—or there definitely wasn’t—it would make no difference to me. I don’t read it for history. ‘Interpretation is an ongoing conversation. You read a passage from the Bible along with the commentary. The commentary is a very big body of literature and takes many years of study. If you read a passage and say, ‘It means x and there’s no other possible way of reading it’, you are excluding yourself from the Great Conversation. You read it in conjunction with the commentary and you compare it and draw conclusions but you do it within certain conventions. There is no one right way to read a text.’ Did she think Richard Dawkins did justice to the sophistication of this approach to reading the Bible? ‘Like the people he criticises, [Dawkins] takes Biblical commentary too literally. He is right to condemn the entry of creationism into science but he has no right to comment “scientifically” on Biblical interpretation.’ It all comes back to the same principle: that religion and science search for truth from two different aspects of consciousness and it’s hopeless to try to criticise one from the point of view of the other. The only way to decide about the truth or otherwise of religion is to test it from personal experience and the only way to find the truth of scientific endeavour is by objective experimentation and testing. There is one final question of truth I need to pose to religion. It is the question my mother asked: If God exists, where was he during the Holocaust? Reading Christian responses to this question, such as the one in Roy Williams’ God Actually, is an uncomfortable business. Although he is sincere in his desire to answer the question, I can imagine my mother’s grim face when he says that ‘suffering begets wisdom’ and ‘that’s how we learn’ and that God gave us free will so that we wouldn’t be automatons (Williams, 2008:210-214). I decided I would feel more trust in a Jewish answer to this question. Once again, I turned to Jewish scholar, Debbie Masel. She sent me an article she had written called Darkness and Light. Arguing from Deuteronomy (30:15; 19):

Debbie says that one theological response to suffering is that God deliberately creates darkness, or ‘hides his Face’ to allow scope for human action. Without this distancing, the human being cannot choose between good and evil. The ‘yetzer’, which could be defined as human passion, incorporates an intrinsic propensity for evil against which one must be vigilant, but it also provides the opportunity for goodness to prevail. This is much the same argument about free will that Roy Williams gives, but one further quotation of Debbie’s seemed to me to answer my mother in a deeper, more fitting way. In answer to the question, ‘Where was God at Auschwitz?’, Debbie quotes Yitz Greenberg: ‘God was there starving, beaten, humiliated, gassed and burned alive, sharing pain as only an infinite capacity for pain can share it.’ Theorising and argument seem to trivialise the pain of Holocaust survivors, even to patronise them. The statement that God was there, also suffering, is almost the only comment I can bear to hear on this topic. I prefer God to be helpless and there than to be omnipotent and cruel.

In 1994, a remarkable thing happened to our family: we discovered that one of Mum’s three brothers had also survived the war, where he had been imprisoned in a Siberian gulag. Afterwards he had walked through Siberia, Kazakhstan and across Europe to reach Israel, enduring hunger and terrible hardships. When he had nearly reached his goal, he was imprisoned in Cyprus by the British. Against the odds, he finally made a home in Israel, married and had a son. We found this out because his son had searched for Mum for two years and finally discovered her in Brisbane. A joyful reunion followed and our lives were changed forever by the restoration to my mother of one precious person from her destroyed childhood. Eleven years later, my mother and sister and I met my Israeli cousin and his wife in Dresden to see if we could find the place where Mum had grown up. We knew there was no chance her apartment would have survived the wartime bombing but we had read that streets and buildings had been reconstructed precisely. At least, perhaps, we could find the street. We caught a taxi to our hotel from the centre of Dresden, with its cobbled streets and old buildings, some in ruins still and some restored. It was a public holiday and people were picnicking beside the street, strolling by the river, enjoying sunshine and a holiday atmosphere. At a tourist shop, we found a souvenir map of pre-war Dresden. Armed with this novelty map we set out on foot to find our way around the sites of my mother’s old neighbourhood. All the landmarks of her childhood were within walking distance of each other in the Altstadt, the old part of Dresden. My mother led us confidently along Munzgasse, a crowded street of fancy little shops and restaurants which seemed old to me but must have been restored. ‘Here was my schule,’ she said, gesturing to one doorway. ‘And here was the synagogue. The service was all based around the singing of the cantor. He had a very fine voice … The kosher butcher was here and this is the place where we bought our groceries.’ We walked along the river. ‘I used to walk here with my cousins,’ said my mother. ‘See how beautiful it is: we used to say it was the Venice of the Elbe. And look, here is the Zwinger, the gardens of the palace. The King went to church here.’ We admired the carved stone, the gold-plated dome. After a few false starts, we found the street where her apartment had once stood. None of the buildings were the same but somehow it was important to find the place on the street where she had lived, and we did. We took a photo. Later, we found the graveyard where Mum’s grandfather and father had been buried before the war. It was in perfect condition. We heard afterwards that the Nazis had not destroyed the cemetery so they could check on any names in case of stolen identities. ‘They are intact,’ said my mother softly, standing beside the graves of her family members. ‘They have not been defiled.’ She was weak with relief, faint. I hadn’t realised how much it had been preying on her mind, this fear that she would find the graves had been desecrated; my atheist mother. There were pebbles on the graves, the Jewish sign of tribute to the dead. Someone else had survived the war and visited this place. We put our own pebbles beside theirs. During that journey, we also visited the village of Rozniatow, in the Ukraine; it was the place my mother had visited her grandparents for holidays when she was a child. All the Jewish homes and synagogues had been destroyed and there was no way to recognise the places she had known so well. On the internet, we found a poem by Techezkel Neubauer written about Rozniatow after the war. My Town describes a beautiful hill, thick trees and a field; a marketplace with two ancient wells; three synagogues where the voice of the Torah was heard day and night; small houses with white roofs, sparkling in the sun.

In Dresden and in Rozniatow, I found what I had lost; the thing I had been yearning for all my life. As we walked about, following my mother’s gestures, I recognised it, even though it wasn’t there any more. It’s there in that poem as well. It was a world of safety, beauty and order, protected by God, governed by wise tradition. Pleasures were simple: walking by the river or across the field, eating fluden with chopped nuts and honey or lokshen kugel with sultanas. There were books and work and family, there was right and wrong and on Shabbat there was a day of rest. I know that nowhere is really like that, or not for long. I know there was always a smell of destruction as well as flowers. I know I would probably have rebelled in an Orthodox home, that I wouldn’t have had the freedom I also crave. I know that, in a way, this thing I long for is a dream—although it was real for my mother. But it’s always with me, this dreaming and longing; and it’s what I call religion. * Richard Dawkins, on the other hand, sees religion as child abuse, the root of all evil. He points to the atrocities carried out in the name of religion: executions for blasphemy in Pakistan and Afghanistan, Baptist preachers who scream ‘God hates fags’, anti-abortionists who blow up abortion clinics and threaten to execute doctors, suicide bombers, and creationists. And we can all add horrors to that collection: the Crusades, the Spanish Inquisition, the collaboration of the Catholic church with the Nazis—it’s a long list. But, astonishingly, Dawkins claims that atheism is pacifist: ‘… why would anyone go to war for the sake of an absence of belief?’ he asks rhetorically (Dawkins, 2006:278). He sees science as always ethical and good. He overlooks the fact that the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were developed by scientists and so was Hitler’s racist eugenics. The vicious medical experimentation on prisoners in Auschwitz was conducted by the scientist, Dr Josef Mengele. People have the capacity for evil, and neither religion nor science exempt us from that although, at their best, both attempt to. If we are going to compare the results of religion and science, we need to compare good religion with good science and bad religion with bad science. Among the many kinds of religiousness explored by William James at the turn of the last century, was one he called ‘the religion of healthy-mindedness’. He spoke in favour of it as a practical and therapeutic approach to life. Healthy-mindedness was a form of positive thinking in which people connected with the Universe or the Great Spirit and thus exchanged disease for ease and suffering for health. It’s associated with groups like Christian Scientists, but it’s very similar to what we call New Age thinking now. The religion focused on the power of optimism and it sounds as though many of the techniques for healthy living have since been taken out of a religious framework and incorporated into Martin Seligman’s ‘new positive psychology’ outlined in books like Authentic Happiness. William James would have been in favour of this development as he observed many examples of it having direct results for people in healthier, happier lives. A friend of mine, Joan, practises her own form of this mind cure, humourously calling it Joanism. She believes in a benevolent force that provides if we ‘put our wishes out to the Universe’. She also believes in reincarnation and that she receives guidance from her deceased grandmother. An intelligent, successful businesswoman, she knows her views can sound wacky to others but she points to the results: through a mixture of positive thinking and relaxation of control (to the Universe), she has overcome asthma and solved many serious difficulties in her life. ‘People ask me what if I’m wrong about what I believe,’ she told me. ‘I tell them I can’t see how it would matter. If, when I die, that really is the end of me, I won’t know and I won’t care. But, in the meantime, my beliefs are a great support to me. I don’t inflict them on anyone else.’ Healthy-mindedness tends to ignore evil, or at least not to focus on it. For instance, some New Age publications advise people not to read the morning newspapers as it’s likely to produce negative thoughts during the day. James says this approach is splendid as long as it works but it breaks down when people suffer from acute melancholy. For some people, suffering the despair of melancholy, a religion that incorporates pessimism can be more suitable. He sees Buddhism and Christianity as the most suitable for that purpose. For some of those people, sudden conversion can bring the happiness they lack. I know a man who recovered from a long-term drug addiction, with all the related despair, when he took the 12-step program and became a Christian. I spoke recently to him and his wife and he said he had tried will-power to cure himself many times but that failed. ‘I had to ask for help. It was the only way,’ he said. His wife agreed. ‘You can practise anything, even tree worship, as long as it’s bigger than you. You have to make yourself humble and admit you can’t fix everything yourself.’ I agreed with them that will-power often isn’t much help with changing deep-seated habits but I wondered whether God was the only solution. And yet, talking to them, I remembered times I had opened myself up to ‘it’—something out there—and magical things seemed to happen. Near the end of Varieties, William James declared his own beliefs. He was a Christian ‘of a somewhat pallid kind, as befits a critical philosopher’. His experience was that a connection with God did not alter the outward face of nature but the meaning of it. ‘It was dead and is alive again. It is like the difference between looking on a person without love or upon the same person with love … It is as if all doors were opened and all paths freshly smoothed’ (James, 1960: 453). * This exploration began when I questioned my own enthusiasm after a first reading of The God Delusion. I was curious to find, a few days after reading it, that I was embarrassed by my first reaction to it. I discovered conflicting attitudes to religion within myself; on the one hand I was attracted to religion and courted it, on the other I was glad to join Dawkins in mocking it and demanding its extermination. I wanted to find a position around religion that didn’t require me to suppress any aspect of myself, that would allow me to be open and enquiring and that would be true to my own personal experience. In a general way, I concluded from all my reading and talking that personal religion is around to stay and that it has a valid place in people’s lives, providing meaning at a deeper level than science can do. In a sense, it is like adding poetry to prose. This has not been my road to Damascus. No bolt of lightning has struck me, causing me to change my life. In the end, I find the position I need to take is probably that one so despised by Richard Dawkins, the agnostic. But I can use that word in the positive way outlined by Mark Vernon in his engaging book, After Atheism. Vernon uses the definition for agnosticism of 19th century scientist, TH Huxley: ‘The agnostic is not an atheist but is someone who tries everything and holds only to that which is good’ (Vernon, 2007: 7). Vernon says agnosticism, in this sense, is not just a shrug of the shoulders but a passionate interest in and exploration of truth. One story in his book illustrated this approach in a way that appeals to me. It was the story of how ancient Greeks, including the philosopher Socrates, would travel to Delphi to consult the oracle. The seeker of truth would ride several days through the desert and high into the hills. There he would purify himself in the Castalian spring and pay a fee. Then he bought a goat for sacrifice, over which was thrown a jug of water. If the goat shuddered, that was the sign that the oracle would respond to a question. Next he had to wait for his lot to be drawn. Finally he was ushered into the holy chamber of Pythia, who was sitting on a tripod wearing a bay leaf crown. He could then ask his question, taking the risk that she might not answer. If the oracle did speak, she might say something quite ambiguous. For example, when King Croesus sought the oracle’s blessing on his proposed war against Persia, the oracle said, ‘A great empire will be destroyed.’ Croesus thought that meant the Persians and went ahead with his plan. In fact, it meant his own. An atheist would see this whole procedure as a con job and a very easy way to part a king from his money. They wouldn’t waste their time considering the cryptic utterances of such obvious charlatans. A believer might take the words of the oracle literally, causing bemusement and no end of difficulty. Vernon suggests that the real benefit might not be the advice itself but the commitment to the consultation process. ‘Agnosticism suggests a path in between a believer’s certainty and an unbeliever’s cynicism that simultaneously mirrors the “in-between’ reality” of the human condition’ (Vernon, 2007: 24). Sometimes a list of pros and cons won’t solve a problem but a long horse-ride and some soothing rituals will bring new insights, as long as we are hopeful and open to seeing past our own first impressions. In the best of science and religion, uncertainty is the guiding principle. In 1900, William James said that God had business with people. Perhaps so. For me, it is still unfinished business. *** Works Cited Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion, Bantam Press, 2006.

Gay,Peter. A Godless Jew: Freud, Atheism and the Making of Psychoanalysis, Yale University Press in association with Hebrew Union College Press, 1987. Gray,John. " The Atheist Delusion" from The Guardian, Saturday 15 March, 2008. http://guardian.co.uk/books/2008/mar/15/society Grayling, A C. " The Death Throes of Religion" from Against All Gods, Oberon Books, London, 2007. James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience, Collins, Great Britain, 1960. Maugham, W Somerset. Of Human Bondage, Vintage, 2000. Robinson, Marilynne. The God Delusion (2006), http://solutions.synearth.net/2006/10/20?print-friendly=true Robinson, Marilynne. The Death of Adam, Picador, New York, 2005. Vernon, Mark. After Atheism, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2007. Williams, Roy. God Actually, ABC Books, 2008. *** About the Author

|