| current issue |

| archives |

| submissions |

| about us |

| contact us |

| competition |

Steven Lang interviewed by n a bourke |

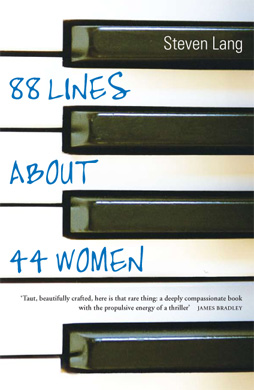

I loved teaching. I loved the theatre of it, the drama of it. Being in front of a class. I loved putting together courses. We had a three hour workshop once a week, and also lectures in different courses. Two hour lectures. But the workshops were these three hour periods and I really liked that. There was time to talk about the process what’s involved in writing. Apart from anything else it made me think about writing in a way I’d never really thought about it before. And then, trying to explain that. Communicate. I would do, say, three different classes, and the one in the morning would be fantastic, and the one in the afternoon would be kind of alright, the one in the evening ... you’d just be dancing around in front of these people and they’d just obviously rather not be there, students in evening classes are almost always exhausted. Gosh, that’s a difficult question. We had a reading-based course, which was the thing. We tried to get people to read. I don’t know how you got into writing, but I got into writing because I loved reading. In fact, I can’t see how anyone else could ever do it. One of the odd things about students was that we would do these surveys – What are the last ten books you’ve read? What are the last two books you’ve really liked? – and find that most of the students didn’t read. They wanted to be writers, but they didn’t want to read books. And they hadn’t read Australian writers. They hadn’t gone into a bookshop and bought books. They might have read some weird fantasy book that I’d never heard of, but that was it. It didn’t just surprise me; it astonished me. Somehow or other the concept of a writer – maybe the writer as celebrity, as some kind of hat to put on to be something – had got into their psyche and so they thought, Oh, I’ll be a writer without having any understanding of why you might want to be a writer. The basis of writing is commas and full stops and sentences. Even more than that, it’s words. It’s putting these words into phrases and grouping them … the awful pedantry of it! You have to like it. If you’re going to do that for six hours a day, six days a week for the rest of your life, there has to be something about it. I mean, my wife says, I don’t know how you do that. How can you? Aren’t you bored to shit with that? and I say, Of course I am. And yet I love it at the same time. How it seems a paragraph is never finished. No text is ever finished, every time I come at it I see changes that need to be made. I mean at the moment, we’re working on the blurb for the back of my new book that's about to come out soon. We must have gone through twenty drafts. 88 Lines about 44 Women. It’s a song title. There’s a song by The Nails. It was a series of couplets about 44 women. And the narrator in my novel was in a rock band; he’s been a songwriter. He’s a musician, and it’s a song that he would like to have written. That’s where the title comes from. Actually he’s quite naïve about the song. The concept behind the title is what he likes, rather than the actual song. It proves to be a rather kinky song about the sexual proclivities of 44 women, which isn’t really what he’s interested in. It’s that idea – I heard it years and years ago – there’s a place outside Melbourne where there’s a big mud brick castle thing – Montsalvat? Something like that. There was a woman who was part of that community that built it in the early days. I remember hearing her when she was about 85 do an interview, and the interviewer said, You’re famous for all the lovers you’ve had. And she said, Well, yes, I know, I probably did sleep with an awful lot of men at different times, but really there’s only one or two that mattered. That’s what my narrator in this story is interested in. No, no, no. The relationships. That in the end there are only one or two. All the rest are kind of forgotten. His name is Lawrence Martin. I think I’ve got a blank of the cover here somewhere. It’s been kind of leaning up against the bookshelf here for the last three months and suddenly it’s not there. Suddenly, it's disappeared. It is very different because it’s a first person narrative apart from anything else, so it’s all one voice. The cover design of a book is always something really, really hard to deal with. Penguin had undertaken to do it without communicating with us very much about it at all. They sent this blank. It arrived, this little parcel. Chris and I looked at it and she said, Open it. And I said, No, you open it. Yes! It’s wonderful. It has a fantastic musical motif. The larger picture, the theme, I guess, is about the difference between love and sex. That’s one of the themes, there’s several others, one of which is clearly shame, but the thing about sex is something quite a lot of people are confused about. Lawrence is one of them. He grew up in Britain but came to Australia in the seventies, joined a rock and roll band that eventually became very successful. Now he’s living in the north west of Scotland, on the edge of a remote sea loch. In the middle of winter. The story is told over three days. Lawrence gave up the rock band after the accident which killed his wife. Now he’s living by himself in this isolated place, getting involved with the woman across the hill, a farmer, and something happens that brings up those former times, so what we get are his thoughts while he’s going through his days. A weave of the past and the present. I found it a very challenging book to write. The time situation that’s evolved. I was interested in trying to tell a story where in the present tense not a huge amount happens. Everything happens in the past. And yet I didn’t want a whole lot of obvious segues, and I still wanted a strong narrative pull. I wanted it to be almost stream of consciousness, where things shift from one time to another seamlessly. It didn’t quite work out that way. At one time during the process I read a review of a book by Mary Gaitskill called Veronica, and it spoke to me very strongly. I thought I had to read it straight away. But after the first chapter I put it down. I’m not normally precious about what I read; I’ll read anything when I’m writing, but this one seemed too close to what I was trying to do. Nine months later, when I came back to it, I wished I’d read it the first time because even though what I was trying to do was similar it was really quite different, and the way she had approached the task was really helpful. This book went through eight drafts or something like that. It changed dramatically because I had a lot of trouble with the action in the present moment. I kept thinking it wasn’t strong enough in itself. I kept – during the first few drafts – I kept having people coming in and shooting someone. I literally had blood on the floor, you know. Exactly. I wanted that. I wanted to have the freedom to have somebody die in the book. You know what I mean? Sometimes literature, all these sort of meaningful conversations between people, can feel really fucking boring while you’re writing it, so I wanted action. I wanted stuff to happen. Eventually I had to grasp that it didn’t have to be like that. It could be just this relationship. Just these simple things. Him walking up a hill, getting in a car and driving, and the thoughts and those things are enough to carry it. It was interesting, because when I went to the editor, when it was eventually accepted by Penguin, and I got an editor, she wanted me to go even further. There were still strands of those stories – like the odd gamekeeper – who wandered into a scene with an old shotgun over his shoulder. Or a rifle. He was still in the story. She said, What’s this bloke doing in the story? She said, There’s too much, you’ve got too many things happening here, which was quite shocking to me because I felt like it was really empty. I found that whole process of the editing, which I had said I really wanted, someone to work with me strongly … I found that quite difficult. Very different. Of course. Which isn’t a bad thing, you know. But for a while there my confidence in my own work was affected. I just didn’t know what was good or bad anymore. I still don’t. I mean, I don’t know if what I’ve finished, what I’ve achieved there is any good. Other people have read it and said it’s good, but I don’t know. It’s like I’ve been so deeply into the nitty gritty of it that I can’t see any larger picture any more. I notice you like Annie Dillard, and one of my favourite books is her The Writing Life. Because she has somehow distilled the essence of what it is to be a writer in there. And one of the things she says is that the temptation to think your work is good or bad are both insects to be treated with the same disdain: swatted away. And I really believe that, because neither of them really helps you. On the other hand, when it takes four years to write a book there has to be a certain belief in yourself: that what you’re doing is alright. Otherwise why would you bother? The book started because I am actually born and raised in Scotland. My family do still live there, and a few years ago I went back. I left Scotland in 1969, so I’ve been here a long time. I was 18. I’m 58 now. Chris and I went back, and one day we went for a drive, out onto a peninsula about halfway up the coast of Scotland, which is quite remote, and the most Westerly point of the British Isles. There is a big sea loch along its southern side. We went for a drive on these little one lane roads in the middle of winter, and it was a miserable day and really rain was just falling. We pulled over right next to the water on this little grassy bit and the sun came out. Lit up the hills all around. These gray, dark skies, and there was sunlight on the water. The cold wind. And I just thought, God, I could live here. For some reason I thought, I could live right here, you know? And I decided to make a character who did that. I wasn’t going to do it, because I have an Australian wife and children and everything like that. I’ll come back here and live here, but I’ll make a character. I don’t think this is unique to me. I think one of the things I do as a writer, is that I decide to put my character in a place, and that character might have several similarities with myself, but he makes a decision that I wouldn’t make, therefore he has to be a different person because I didn’t make that decision. He made that decision, so I then make a life for him that justifies him making that decision. It has to work backwards and forwards and all around from there. And so, I write from a character point of view, it’s more than just a situation. Although the next book I’m going to write will be a plot-based book. I’d love to try. I find plots so hard. It’s a book about Lawrence Martin and about being in his head, but I didn’t trust that what was in his head was going to be interesting enough so I wanted something exciting to happen to him so I didn’t have to spend so long inside his head I suppose. Funnily enough, I made Lawrence an Englishman who just went to school in Scotland, boarding school because his mother was Scottish and his father was English and he was sent up to boarding school. Which is where I went to boarding school from when I was 9 until I was 17, which was what middle class people do to their children in Britain. To their children. It’s not a good system. I’m very opposed to boarding schools for young children. I think they do have their place for older children. I think teenagers, particularly, when they are a bit older, benefit from it enormously if they want to. If that’s what they want to do, because it focuses them. Somehow children need to get out of the nest. And that’s quite hard to do. What I was saying was that I find Scotland incredibly – the islands, the hills – it has an incredibly profound effect on me. I love walking. I do a lot of walking, all over the world, but I get up on a hill in Scotland and I feel more alive there than anywhere else and I have no rational explanation for it. It’s not something I’ve wished upon myself. I’m an Australian citizen. I’ve been living here for 40 years, but I go back there to my family, go and see my father who’s 91, walk up a hill and suddenly I’m singing, in my soul. Something really vibrant happens. The cold air. I love climbing mountains. Hill walking. I do get a sense of exhilaration wherever I do it, but it’s unmatched compared to what happens in Scotland.

I’ve given him that attribute. He doesn’t really know why he’s done what he’s done. He’s trying to figure that out. He’s got involved with this woman, who lives next door, without really meaning to either, that’s kind of what he does … He’s the kind of man who needs to be in a relationship with a woman at all times, and really chooses his partners from a sexual perspective and then ends up with a person he has to deal with. As a result he’s been something of a serial monogamist for some time. He falls into relationships with people. I grew up through the 60s, 70s, 80s. It was a very promiscuous time, and with this idea that we could have sex with as many people as we liked and it was fine, but my experience turned out to be that if I entered a sexual relationship with somebody it wasn’t as simple as that. Other parts of me got involved that I wasn’t so aware of. It’s not easy: you can’t just kind of pick up and put people down. Well, I can’t. Lawrence can’t pick up and put people down the way that other people seem to be capable of doing. Though I don’t really know; I don’t anybody who can, to be honest. Exactly. Oh Absolutely. I think we really hurt ourselves a lot because of that, because it was part of our ethos that we should be able to do that. I think it’s interesting to hear you say that as a woman, because I think there was even more pressure on women in that respect because the pill had come into being and there was this sexual revolution where people were able to have sex without getting pregnant, and therefore women had this capacity to explore their sexuality with a whole lot of other people and yet women are much more susceptible to that syndrome I was talking about earlier, becoming involved with people. That’s a very neat way of putting it, I think. I wanted to call this novel The Law of Unexpected Consequences, Penguin wouldn’t let me. We had a lot of discussion about the title. I thought The Law of Unexpected Consequences was a great title, a little long, but there are a lot of long titles. It is actually a phrase people use, you hear it around the place. It has a rhythm, meaning, too. Because it’s that thing that happens. You set out to do something, and something else happens. All the time. But they said it had too many negative words in it. Law and Unexpected, and then Consequences … I came up with that quite late in the piece. But this song title [the eventual title of the book] was always in the book. It was an alternative in some ways, because it’s such a catchy title, and I’m always going to end up having to explain it. People are going to say, Oh, you’re writing about your lovers and your life – all that kind of crap. We can get round that. I want to try and learn some of the lyrics to the song. No, no, no. Just as an example. I did download the lyrics, I’ve just got a few of them here:

That sort of stuff, right? There’s a whole lot of them. I’ve chosen some of the less sexually-explicit ones. There’s a passage where Lawrence and the woman – Sam – are in a little seaport in among the fishing vessels, and it’s a kind of special moment. They’re walking along the wharf, hand in hand, life is going on, and Lawrence is talking about that idea that there are only so many times you can do this with people and have it be significant. Or walking along the sand, having dinner. There are these kind of iconic things that people do together, but if you do it with too many people it just becomes something you do, rather than something special. Lawrence muses on the song title at this point, and on his relationship with women. I mean … I won’t say anymore about it now because it’s quite an essential part of the book. Him thinking about those things. And also because he’s 49, just about to turn 50, and his capacity to remember who the various women were, even what their names were … Lawrence looks back in his mind and he says, I used to think that all the relationships I ever had were in some memory vault and all I needed to do was open the door and each one of them would come out complete with person, situation, name – all that – and he suddenly finds that they’re not all available. They’re kind of jumbled up. Some of them have lost their names, and some have lost the place where they occurred. Memory doesn’t actually work like that. Yeah. I don’t think that’s anything to do with senility. It’s just that life has that form to it. One of the interesting things I heard recently was this phrase: the fascism of memory. It really caught my attention, because the most obvious place this happens is with your partner. You’ve both been somewhere together, and you say Deirdre was there, and your partner says Deirdre wasn’t there, and you say, Excuse me, I was there, and I saw Deirdre. You know that, because you can see it clearly: Deirdre standing there, saying something. That’s what the fascism of memory is. You’ve got it in your mind so it has to be true. Yes – and often it turns out Deirdre wasn’t there at all and you’ve got it mixed up with some other situation. Happens to me all the time. Yes, and yet memory is so powerful. We have a memory of something and that is how it was. The idea that that memory can somehow have been elided with other things … I like to think of myself as someone with moral integrity. I don’t like to think of myself as someone who would mix things up. That’s true. That’s also an excuse for dishonesty. It’s something I quite like to write about. It’s something I touched on with Lawrence, but not something I’ve explored a great deal. I mean, the trouble is it’s a bit of a trope: memory, in terms of writing. What I did at that point was to write a draft of the novel, with various threads of story. I sit a person in a situation, and I say: Who is this person? Where are his mother and his father? Where is he? What is he doing? Maybe not as coldly as that. I find the whole process terrifying, I have to say. I’m not one of those people who relishes going down to the studio to write. I mean, I do, I love going down there to write, but I don’t like what happens when I’m down there. I heard on The Movie Show about two weeks ago this young man – how he could possibly know this at his age, I don’t know – he was talking about Keats. Jane Campion’s just made a new film about Keats. Ben Wishaw was his name, I think, and he’s the man playing Keats, and he’s talking about Keats’ idea of negative capability. He articulated negative capability in a way that I’d never heard it done before. On The Movie Show! This young whipper-snipper! Articulating something that I find really hard to put into words. I don’t think I can even say what he said, but the way that I would say it is that a human being likes to be in control. We like to know what’s going on at any given moment, and the process of writing is going to a place of not-knowing. In order for a thousand words of any value to appear at the end of the day, I have to go to a place where I don’t know, and allow something to happen. I think that’s a very unnatural place to go to. Not just for me, but for any human being. I think that’s why artists are naturally drug-takers and drunkards and things like that, because we’re naturally a bit closer to that edge than everyone else. I don’t happen to be one of those. I’m not an alcoholic, or a huge drug-taker. I can see why one would want to be. That door is a very uncomfortable place to sit. But it’s also very exciting. Because that’s where the interest is. It’s where the whole essence of what happens is. That’s what’s exciting about the process. That’s why I want to go there. That’s my process; I’ve come up with an idea for this character I’ve decided to call Lawrence Martin, and I’ve said he’s got a friend called Roland. Then I have to make up Roland, so I think about Roland and the situation he’s in, and this great fucking critic is sitting on my shoulder, saying, Oh, that’s really twee, that’s boring, that was in that book, you’re trying to channel Trollope, whatever it is, you know? I try and put the critic away and just write. Anything, really, about Roland that I know. Sometimes things come down. A little scene comes down. Roland will appear and that’s him. That’s what I work with. Then I fit them together. I say, Well, if that’s that person, and Lawrence is this person and they do this thing together, how does this dynamic go in? And then I remember friendships that I’ve had, and how that dynamic has been. There’s a kind of collision going on there between these people that I’ve created and my own memories. I’ll write a draft and realise it’s not working. One of the things I would tell students was to try and be present in the scene all the time. Just ground yourself in there. When I’m writing I find the words often carry themselves on, and I’ll write a sentence of dialogue and then another sentence of dialogue will follow from it, this flow of stuff going on, which is actually nothing to do with the place where it’s actually happening, but I’ve fallen in love with this patch of dialogue I’ve got. Fallen in love is too strong. I mean, I like the dialogue, and I’m so pleased to have something down on paper that I’ve forgotten the two characters are sitting in a farmhouse and Lawrence has gone there with this or that in mind, and therefore it’s not going to follow that path or direction. In that situation he wouldn’t say that, no matter how pleasing it is to me as a writer to have him say it. I think so. Yes. Do you find any kind of resonance in what I’m saying here? I think it is a very curious thing to do. It’s also an incredibly time-wasting thing to do. I will set myself to sit there for five hours or something, and really, most of the writing gets down during a forty-minute burst somewhere in the middle of that. The rest of it is kind of wasting time. Don’t even ask. Look at the news on the internet, send email... I didn’t used to have any internet in my office, which was much better. It’s a terrible distraction. And email! I read a report that said after one email it takes twenty minutes to get back to work. I think that’s really minimal. I think probably an under-estimate. I think forty minutes. Yes. You think: I’ll do something useful now. Just send an email. I have another friend who’s also a writer, who says to me, You’re doing it for all of us. There need to be people who can do that. Our culture really needs people to sit in rooms by themselves and struggle over this stuff. Remember that, when you’re sitting there being hyper-critical of the fact that very little is coming out of this process. The funny thing is, it feels like very little, but at the end there’s a book. That book only took two years to write. Two and a bit. Before I sent it off and it was accepted by a publisher. Another 18 months after the publisher accepted it to get published. In the meantime I haven’t really written anything else. I’ve done three drafts of it since then. Three complete drafts. It was accepted at the fifth draft. The first one was just really a mish-mash, the second one I could kind of see what … One of the metaphors I would talk to students about was that one about Michelangelo looking at a block of granite, and somewhere inside that block there’s a figure and all he had to do was chip away to find it. I think that with writing you have to make the block of wood. That’s why writing is so hard, because you actually have to create a body of work in which a story lies, and then chip away and find the story within the mass of stuff you’ve done. So, I think that process of the five drafts is doing that. As I say, I was working with a lot of different times. I had present time, which is the three days that he’s in, and then there’s the time during the last three months while he’s been in Scotland, there’s the time when he was with his parents back in England, who are old and living in a small aged care facility, and there was the time when the accident happened, which is 18 years ago, and the year of their relationship – him and his wife, leading up to the accident – from when he met her to then, and his relationship with Roly within that period. Then you jump back another 12 years to arriving in Australia and all this time here with Roly, and back to the time when he was a child at school in London. All that life was set in different time zones and getting the story to move through that, from the perspective of the present, was a struggle. Fascinating, like a jigsaw puzzle, but it did take a lot of drafts to get it right, to get it in order, to get it feeling like it was going in the right direction. I print it out when I finish. It takes about three months or so for me to do a draft and that’s a process of printing out, working with a pencil in hardcopy, putting those corrections in, rewriting whole scenes, creating new scenes, bringing in characters, throwing some out, things like that. Eventually there’s a point where I say, Done! Put that away. I would leave that for six weeks or two months before I’d even look at it. I didn’t let anybody else look at it until the fifth draft either. I don’t like other people to see it. I don’t let me wife, Chris, read it until I’m ready to send it off. Because I’m too sensitive to other people’s viewpoint. It goes back to that space of unknowing, because the whole process is so fragile and if somebody came along and said, Oh, but that character, Sam, is awful, like that woman in After You’d Gone, Maggie O’Farrell’s book. I would actually kill Sam. I mean it, I would. In some way or other. I’d do something. Yes! Sam is a creation in process and at some point she’ll be finished, but I have to be the one who decides. She might change into something completely different, but if somebody comes along and is critical of her, then I immediately change my whole viewpoint on her. There’s a time for that and that’s during the editing process, when I want people’s feedback, when I feel confident enough that there’s a story in there. After that, I really like the rewriting period. I know that might sound odd, but I find it a lot easier than writing. I’m so pleased we agree on that, because as I said, I’m writing a plot-based novel now, just coming up with a plot. Oh, fucking oath! Hair-pulling stuff. And simple stuff. Really simple adventure story stuff. Getting in and out of a room at the right time in the right place, in a believable fashion. It’s not actually as hard, because I have written two books that have been accepted by publishers and people have liked them who don’t know me. Who weren’t my friends. Somebody was prepared to pay money for that book, which means that it had value. That’s awful, but it’s unbelievably important. I don’t like it being important, but it is. That gives me courage. The reason I started writing so late in life was that I used to get really frightened; I would go into these places and I didn’t believe in my own worth at all. I would sit there for months, trying to plot and make things up, and I would say, This is garbage; I’m going to go and do something useful. And I would stop. I’d been writing all my life. I’d always wanted to be a writer. I mean, I wrote my first novel when I was 16 or 17 in boarding school, in the evenings. It was about four people who met in various different places in London and each one went off to live by themselves in remote parts of the world. Northern Canada and places like that. Hermits. It was a terribly sad little book. Yes, a very lonely book. It speaks to where I was at that time in my life. Interesting, too, because I was born and raised in Scotland. I think two of the characters meet in a park in Knightsbridge or somewhere, one of those big parks in London. One of them is walking naked there in the moonlight, because this is the symbol of freedom. He’s thrown off his clothes and somebody else meets him and a relationship develops out of that. Not a sexual one, but … oh well, perhaps a sexual one will eventually develop. But that idea of throwing off one’s clothes was really significant. Of freedom. I like coming to Australia, where you don’t have to wear clothes for several months of the year. There was nothing much after that, and then when I was in my 30s I started writing a journal and I wrote in a quite disciplined way. Every day, basically for ten years, sometimes 3000 to 6000 words a day. It might be as little as 600 to 1000 words, but often much more. I would write down conversations. Instead of listening, I would – at the end of the day – write it down. What I remembered of what you said. I always wanted to write, and I just found that writing a journal - well, I found I was good at it. Yes, I think so, much less confronting. Because I was writing about something I’d seen. I didn’t have to make anything up at all. When I first started I couldn’t remember, at the end of the day, what anyone else had said. I had to train myself to listen. I’d just like to say, you’re very good at it. I’m sitting here talking away, you’re very good at just getting me to talk. I don’t normally mouth off quite so readily. But, I got quite good at asking the right question, at listening, drawing things out of people, listening to their intonation so that I could put it down. Particularly in relationships. The women that I was wooing. I would write down things they would say. Oh fuck, it’s dreadful. I’m such an awful person, really. It wasn’t really that bad. I was doing it because I wanted to write and it was so meaningful to me. Everything was so important. And people kept giving me really good feedback on what I wrote in my journal. I would read it to people, not show them. It was all hand-written, huge amounts of it. I think they just liked the descriptions of them and the fact that the description of an evening – seven different conversations. It was just. I would sit down and write 6000 words in two hours. No chronological order: one thought leading to another. People saying that, leading to that, and this scene. I had no struggle over it. I could just do this for days, but it never went out. It wasn’t going anywhere at all. I did do a big road trip with a girlfriend in the late 80s – we went up to Kakadu and through the centre – and I decided I would try and make that into a book. Computers had just been invented, so I bought a PC and paid somebody to type two journals up and give me the digital file for it. I formed it up into a sort of document, which I sent off to various people, and nobody really wanted it. I could see why they didn’t want it. It didn’t have the structure. I started to realise the tyranny of truth. Because these were real people, real events, I couldn’t move them; I couldn’t make them do things for the sake of a story. They had to be what they said, where they said it. I realised I had to move into fiction, but I didn’t have the courage to do that. Every time I would sit down and say, Ok, now I’m going to write a novel, I’d get… I mean, some days I have to sit alone in a room for days before something will start happening. There’s words going there, but it doesn’t feel like anything is happening, it feels meaningless and it might take a month. I was just saying that the new book I’ve been working on for a month and I don’t feel like there’s anything there, but when I go back I realise there are the bones of a story in there. I haven’t got to the point where I can say, Well, let’s start writing. Let’s do this. And in fact you never really hit that point until it’s finished. That’s part of the myth of it. When I didn’t have any confidence in myself, I’d do this for a certain number of days and then I’d just walk away. I couldn’t make myself go and sit down there and do it. I couldn’t force myself to do it. I would go and do something else. Something useful. I think my first thing was film script. Well, I wrote my first public work was A Strong, Brown God, which was a walk down the Mary River. I wrote that, which was basically a journal. After that, my good friend Gerard Lee had done a lot of film writing, and he talked to me a lot about the structure of films, particularly the three act, restorative plot. And I thought I would do that, and it was one of the best things I’d ever done, because on page 29 there had to be a plot point, and then this, and then page 82 another, and then a resolution. It meant that I could make stuff up that would do that. I realised the freedom of fiction: that is something’s not working – Henry – let’s get rid of him, or make him Henrietta. What it really is is the wonderful freedom of writing fiction, which is at the same time a terrible burden and an amazing freedom because they’re just chips on the board and you move them around where you need them to be in order to get the story going. Some of those chips become so big you can’t move them. Everything else has to move around them. But that’s part of the process as well. It was the first time I’d ever successfully done it. I don’t think the film script was great. I sent it out to some people and they sent it back. Of course at that stage, a knock back was enough for me to put it in the drawer and say forget about it. Out of that I wrote An Accidental Terrorist, because I felt like I had the tools to write it.

I was naturally a prose writer, rather than a scriptwriter. Towards the end of An Accidental Terrorist, I did my Masters in film writing at QUT. One of their one year courses. I wrote another film script. Once again, I don’t think it’s a particularly interesting film script, but the discipline of it was fantastic. The structure of having to tell the story in this way, having to make it work. Funnily enough, I do, but it came to me through writing for film. I think because the film script structure was so simple in some ways. In fact, the second one that I wrote … Do you remember when Pulp Fiction came out, and everyone thought it was an incredible film because it was a film like a novel. I thought, how boring is that? I’d been reading novels like that since I was 10. Tarantino has not done anything so incredibly radical. What I did, as part of my masters, I wrote about that idea – the idea of the linear narrative – because nearly all films up until about 1998 or something are all just linear and chronological. I said: what happens if we alter that, shift these things around, because that makes things more interesting? That’s what I did with my film script. It was wonderful, because it was three different timelines, but I didn’t care because suddenly it was like I was working with the building blocks of fiction in a way that allowed me to play. Just like an exercise. Like doing yoga or a warm-up before doing exercise. I didn’t mean to be. I didn’t set out to do that. Which is much easier, I think. Much easier to write. Don’t you think so? I’m reading a book at the moment that I’d quite like to show you. The Secret Intensity of Everyday Life: a dreadful title though. Kind of like The Law of Unexpected Consequences, now I think about it. What the author does is that every person you meet gets a chapter. Yes, but in The Secret Intensity of Everyday Life the author’s in a small village and every time anyone bumps into someone else you get a chapter form their point of view. The funny thing is, he does it quite well; I’m really impressed. I didn’t know if I’d like this. [ Steven gets out the book and we open it to a page that is in first person] Gosh! I didn’t even realise. I thought it was all third person. Although I think one of the children is written in first person. Much easier with multiple people. Standing outside that person, there’s that capacity to use free indirect speech, and you can also go into someone else and see the same situation from a different point of view. Something can happen in the novel that this person wasn’t involved in. First person is very limiting and liberating. You can talk about anything you want to. When I completed the novel – 88 Lines About 44 Women – I sent it out to a few publishers. That was when an agent would have been really useful. It’s just a small scene, isn’t it? Do you go to Brisbane and schmooze? Does everybody know you? That’s an incredible workload. Aren't there something like 90 novels? . Presumably you can narrow that down to 10 in a very short time? I used to say to students that you have to make sure that it’s in 12 point font, Times New Roman, all that, if it’s not, nobody will look at it. I wouldn’t do it. I think it’s an awful job. It changed my life completely. A huge bolt of confidence. I always think of that day you and I spent with Gary Fisketjon, the editor from Knopf. Before [my first book] was published. I hadn't won the award, around 2001/2002. Sam Wagan Watson was there, yourself and me and Gary Fisketjon and a couple of others. He edited Peter Carey, Ian McEwan. Those things. Winning that award. I just think confidence is an incredibly difficult thing. Just believing that there is a point to going back into that room and sitting at that desk again, that it is meaningful to someone else and not just me. Maybe I’m just someone really lacking in confidence. It took me a long time to get it or something. But those experiences. Hilary Beaton was the director of the QWC and she was the dramaturg on A Strong, Brown God. She must have liked something about my writing. She became an advocate for me, got me to do Wordpool two years in a row, introduced me to people. It was combination of Claire Booth at the Premier’s department and Hilary Beaton. They both decided that I should go on to that. I think that emerging writers need an advocate. That’s why I think it’s a wonderful thing you’re doing, giving support to writers. You would have been part of the panel that gave the award to Karen Foxlee, then? She was a student of mine. I told her she should enter the award because I thought she was incredibly talented. I still think she is. I think the unpublished manuscript award is a wonderful thing. It was the first time I’d ever really won anything. It was like a huge raffle. I bought a beautiful laptop. Spent $4000 on a Toshiba laptop. Loved it. I wanted to get published! Penguin, Allen & Unwin, two or three people. I remember getting a letter form A&U saying they didn’t think there was any market for stories about eco-terrorists. It was one of those letters saying: I don’t know how we’ll pitch this book. I don’t think there’s a market for it, or something like that. And you just think, Well, fuck off, you just don’t want to publish the book. Just be honest. I am a bit older than you and I hadn’t been published. I was in my 50s already, and I’d always been a kind of writer in waiting. I was working as a creative writing teacher. It just meant that suddenly I didn’t have to apologise for spending that time in a room by myself. Five years. I got into it because I’d done A Strong, Brown God and I’d written some short stories, and I’d organised a writers festival up here. The Maleny Festival of Books and Writing, in 1999, I think. 98 or 99. I got to know Gary Crew during that, and he said to me, I think we need to employ somebody at the [Sunshine Coast] University, do you want to come and do an interview? So I went and did an interview and they chose me, which was great. I’d dropped out of university. I’d gone back in my 30s and dropped out. So, I’d been teaching there on the basis of industry knowledge. I got a grant from the RADF to make a DVD of A Strong, Brown God about three years ago. I had this idea that I would just talk the play into a microphone. I’d go to a sound box and read it, then put all the slides into a slideshow, put it up on a screen and just have the play going on. They gave me $5000 to do it. Then I realised that nobody was going to look at this. People need much more from multimedia than just a slide show and somebody talking. I thought I had to do something else. I thought I could do some videos and then the Beattie government announced the Traveston Dam. I realised that the play was no longer valid in any way at all because the Mary River is now about Traveston not about anything else. I just couldn’t deal with it. I spent the money, quietly. Eventually, I went back to RADF and said I hadn’t done this, but I need to acquit the grant, how can I do it? John Waldren has come up with a solution, which is that I’m going to produce a book, and that’s what I’m working on now. This is what I’ve got here on my desk at the moment. Just putting it together. I’ll self-publish it, using InDesign, putting the text and the photographs together. It will cost a bit to print it. I’ve also agreed to do three performances. The Sunshine Coast Regional Council are putting together a festival of trees: Treeline. May next year. And they will advertise me, they’ll put on the venue. I just have to show up and do the performance. I’ll have to work up to that. It’s been a long time since I’ve done it. Anyway, this is the stage I’m at at the moment. I promised that I’d do it by the end of June, but I think it’s going to be the end of July. It’s a very interesting process. I get really fascinated. I can sit at the computer, playing with InDesign for hours, with the aesthetics of it. I’m kind of pleased with some pages, now, they’re alright. I kind of enjoy it. There’s still an edge. If it’s not nice, people are going to think I’m a bad person. You know what I mean? There’s a voice inside my head that says they’ll think I’m a wanker, or whatever it is. Whatever the thing is that you don’t want people to think. That’s what they’ll think of me. Do you read New York Review of Books? I really like the physical paper. I change all the time, from the London Review of Books to the New York Review of Books and Harper's. I’m on Harpers at the moment. But I’m going back to the London Review of Books for a while - I can only have one - and The Monthly. What annoys you about it? Indulge me. I read Gideon Haigh’s long thing on Crikey – he’s so articulate, I’m completely in awe of him – it was interesting all the comments underneath his thing on Crikey. It did smell awfully like academic politics. And there’s such good writing in it. It’s the only magazine that in any way can be compared to those international magazines we mentioned before. Let me explore that for a moment; can you tell me what role you see Perilous Adventures playing, then? I got the Queensland Writers Centre magazine yesterday and I noticed an insert in there, advertising some kind of writing courses or workshops. It was very different to what you’re doing, less about becoming a professional writer, more about getting in touch with your creative soul, that kind of thing. That’s a lovely notion. I’m going to play with that for a while, if you don’t mind. I’m not quite sure I agree with it, because it’s very abstract to think of giving the writing away to someone, but at the same time I think there’s definitely a point where the writing is … That’s the difference between writing a journal and writing fiction. As soon as I started writing fiction I was writing for somebody else. I noticed on your website that you like Margaret Atwood. I love her work, especially The Blind Assassin. Because of the time – the way that she plays with time in that book. But also the way she plays with historical artefacts, like the newspaper articles and things like that. Funnily enough, we bought some talking books for the shop. One of them was The Blind Assassin, and the reader is a Canadian woman. Having read the book – and I don’t know if you’d get it if you hadn’t read the book – I just loved it. Listening to it the second time. That sense of the passage of history. These people who had the button factory and the big house, and then she’s a woman walking along the road. I think Ian McEwan uses that same motif in some ways, of the girl who was part of the big house and then goes back and it’s a hotel. It’s something of the same motif. Atonement, I have to say, is probably the one major work of our time. I think Ian McEwan is an extraordinary writer to start with, and so far it’s his best work. The whole thing is the unreliable narrator, it’s the essence of that all the way through. Do you ever read James Wood's work? He wrote a piece on Atonement, in The New Republic. I think he says much better than I could say what I think about that book. I just felt he had nailed it in some ways. It crosses so many different genres. What Wood was talking about is that at the end of the book you realise that it’s all a fiction. That this has all been Briony writing this the whole time, and that Robbie has never met Cecilia again. He has never got to meet Cecilia again. This is [Briony's] attempt at atonement for what she did: to try and create a happy ending for them. You realise you’ve been fooled, but you wanted to be fooled. There’s a complicity going on between the reader and the author in the idea of story, and at the same time there’s this wonderful tapestry that you’re part of. I just love it. Not the work, necessarily, I don’t mean that, but one of them. It’s interesting. When I was growing up, Somerset Maugham was a really big writer. I read a lot of his stuff and now nobody reads him at all. There are all these people – all this struggle that you and I are engaged in is really very time-sensitive, and getting more and more so all the time. If you ever run a bookshop, you’ll know that things don’t stay on the bookshelf for very long at all. Unless it’s a shop like ours, which wanted to be a kind of library, to have a solid backlist. There aren’t many shops like that around. I don’t think there are so many people whose books will survive our time, and I think that McEwan is one of those authors who will survive. Not necessarily all of his work, but Atonement, certainly. I think Atwood will as well. I would suggest that The Blind Assassin is a book that will survive. It’s already been forgotten, but I think it will come back. I think it’s a book people will come back to. Maybe I’m wrong. Probably my favourite writer is Saul Bellow. It’s interesting to see how unread he is. Very few people seem to know who Saul Bellow is. Other writers know. He’s one of the majors of our time. If not the major writer of that period from 1950 – 2000. Humboldt’s Gift (1975) gets to me again and again. I read it for the fifth time last year and Chris said, You’re not going to read that book again, are you? I love the language. The Adventures of Augie March (1953) is one of my favourites. I didn’t realise it was his breakthrough novel; I thought it came later. It never occurred to me that someone could write that well, when he was that young. That’s extraordinary. In the broad terms basically, I want as a writer to talk about what it was like to be alive, and nothing else. Secondarily to tell a story. I’m acutely aware that the writer’s job is to entertain. I think that in the late part of the twentieth century we forgot this, and thought that we would get rid of narrative and all of that. Sorry. I’ve never subscribed to that philosophy and I don’t want to. Writing is supposed to be a joy to read. Something that passes the time, but it should enliven and enrich at the same time. I want to do that. I want people to pick up a book of mine … When I was a younger man if I read a good book and finished it, turned the last page, I would often, almost involuntarily, kiss the back of the book. It was an expression of thanks. Thank you for what you’ve done. To the book. Not to the author, even, but to the book. Thank you for what you’ve given me. I want to be able to give that. I want somebody to feel that about a book I’ve written. I don’t know if I’ll ever achieve that.

The point is that I want to be part of that conversation. It’s such a weird aspiration: to want to touch the nameless masses. What’s wrong with me that I can’t be content just being here and having my own relationships with my family; why do I need to get out there and touch people? It does because one of the things we’ve been talking about today is how long – how much of our lives we spend doing something we know is really ephemeral. I remember the Balinese artists, years ago, who would never put their names on their work. The work was what was important, not their name. How extraordinary that is. Can you imagine writing a novel, and not having your name on it? I think as I get older I could possibly do it, but I certainly couldn’t have done it at the time my first book was published. Because it’s also that thing of how will you be paid. And, oh dear, I need the recognition. I need to be acknowledged by people. That I did it. I think that that acknowledgment is necessary. I’m very happy to sit in that room for three years without anybody seeing what I’m doing. But when it goes out there, I want somebody to say it’s good. I wouldn’t like to be a painter. An artist. I mean, I go into a gallery and swan past these works. Each one represents hours, months, days of work and I just think, Oh no, I don’t like that one, and keep moving. God knows what people are going to say about this new book of mine. It was, there are extraordinarily glowing quotes from reviews on the back of the new book. There were a couple of reviews that were so-so, it wasn’t all glowing. But there was nothing bad. There was one in The Courier Mail that was kind of more negative, but who cares? There were no hatchet jobs, so it’s a bit scary to go out there again. I was asked to review some books by Overland. I was asked to review [Richard] Flanagan’s The Unknown Terrorist and [Andrew] McGahan’s Underground, and I was quite scathing about them. I said that I thought they both had a message they wanted to get across and that they had decided they would write popular fiction in order to do that. I said I thought that it showed. You know, that they didn’t really respect the genre they were writing in: that in some ways they were slumming it. The sub-editor picked up that line, so the title of the review became ‘Slumming It’. In the review, I said that I thought what they were writing about was serious, and needed to be written about, but they weren’t particularly successful at it, in either case. It was an honest opinion, but when I think about it I wouldn’t want someone to write about me like that. It’s very hard to be honest. I wanted to say these were really serious considerations, and these were/are both good writers, who’ve done this work, but they’re misguided in their approach here. I think Richard Flanagan, though, is a wonderful man. Did you read his speech at the close of the Sydney Writers Festival? About parallel importation? He wrote that piece about Gunns as well, for The Monthly. So, it’s quite hard to write reviews in this country, where you’re likely to bump into the author. It is a very small community, everybody knows everybody’s business. More Author Interviews Gary Crew interviewed by n a bourke (Issue 09:03) Patrick Holland interviewed by n a bourke (Issue 10:03) Belinda Jeffrey interviewed by Inga Simpson (10:02) Susan Johnson interviewed by Sandra Hogan (Issue 11:01) Krissy Kneen interviewed by n a bourke (Issue 09:05) Steven Lang interviewed by n a bourke (issue 09:04) Pippa Masson interviewed by Janene Carey (10:02) Lisa Unger interviewed by Inga Simpson (10:01) Charlotte Wood interviewed by Sandra Hogan (11:02)

*** |