| current issue |

| archives |

| submissions |

| about us |

| contact us |

| short story competition |

sponsored by

On Not Writing About Sex by Krissy Kneen |

|

My friend Chris insists that when I write about sex I am never writing about sex. This seems ridiculous. I have spent over a year and a half writing a true short story about sex every day. 511 blog posts religiously posted to my website on a daily basis. I have a sexual memoir published. I seem to have become the go-to person on anything to do with sex writing. I have reached a point in my career where I can claim pornography and sex toys back on tax. They have become tools of the trade, my trade, the writing-about-sex trade. There are so many different types of sex writing. There is the blunt, purpose-built pornography that you read in what I fondly call ‘stick-mags’ those cheap little black and white things we buy mostly for the grainy pictures of fucking, but occasionally for the lewd ‘reader’s’ letters and descriptions of sex designed expressly for masturbation. I quite like these magazines. There is something irresistibly furtive about them. I like the ludicrously always-perfect sexual encounters. I like the bawdy talk and the lack of skill in the execution. I like that they are unapologetic about their purpose. It is as if they are saying “here is this story, it is made for you to masturbate over. OK. Here is the cumshot. You can stop reading now”. This is not the kind of writing I do. I suppose I have modelled myself most closely on the work of Anais Nin. I am fond of the fact that her sex stories were written for private collectors. There is something in that which gives it an extra erotic charge: sex written in private for an anonymous other. It is like walking up to one of those walls in a sex club where there are holes cut and genitals offered through them. A thrilling anonymity. A clean easiness to doing it then walking away from it unscathed.

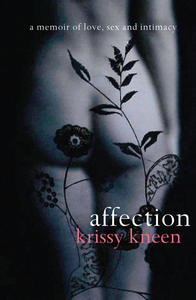

Here is an example of how I make love. This is from my memoir, Affection: A Memoir of Love, Sex, and Intimacy

In this example, sex is the setting. Its not implied or sublimated by metaphor. Sex is the thing that is described in detail. The body of the girl is (like) the landscape where the action is taking place. I describe her body as I would an inner-city alley, or a forest, or the various settings that provide a location for a story. I focus on the details that will make the story real for an audience. I put enough information in it so that a reader can feel oriented in the landscape. The tricky bit is what to leave out. Leaving space. I think this might be one of the only rules I strictly adhere to when I am writing. Space for readers to sink into. Space for them to slip into my skin. They want to touch what I touch, bite down into flesh or slip their fingers into one place or another. They want me to lead them to the adventure and to stay with them while we are there. But in the actual act I must hold back. I must slip in one finger and allow space for two of their own. I must kiss one breast and leave the other free for the reader’s mouth. Sometimes our lips must touch over a single nipple. Writing is like doing. When people share partners they should not be greedy. They must leave space for the other. There is a fine line between leading the reader and allowing them to find things for themselves. If a writer’s structure is too flimsy it will fall apart. The reader will lose interest if there are not enough clues as to what is happening in the scene. So there must be a balance between showing the reader and allowing them to explore for themselves. Spelling everything out does not allow the reader to participate. They become a voyeur. This is not always a problem. Sometimes it is fine just to lie back and let pornographic writing wash over you. It does the trick if the aim of the exercise is purely masturbatory. But what is left unsaid and the whiff of a subtext can give a reader the chance to actively participate in the sex that they are reading. If details are artfully left out of the text then the reader is given permission to add their own colour to the scene. When I was a child my mother taught me how to draw. There were lessons about craft, about composition, colour, texture, all elements that can be translated into the art of writing a story. But one thing she told me stands out in my memory above all other things. I was drawing a still life. I was competent with pencil. An apple looked like an apple. Still, she stopped my hand and pointed and said, “Look. You are drawing the object, but see, it is more than an object. Anyone can draw an apple. You are looking but not seeing. Half of the picture is all shadow, the way the light falls on the fruit, the spill of darkness on the table”. Likewise, anyone can write about sex. Sex is about genitals and friction and a climb towards orgasm. It is the writer who looks to and alludes to the story behind the story who will capture our imagination. Sex is the coming together of (two or more) people who bring their (various) shadows with them. The trick is to be able to paint with words, the way the light falls on two or more people, the spill of darkness on their bed. Words. But not too many of them and just enough so that the reader will notice the shadows and come to their own conclusion about the subtext. It is easy to lull a reader into a sense of security. Measured sentences, a steady escalation. A clean, easy journey you are taking together. The warm comfort of this kind of writing provides few surprises. The predictability lulls the reader into complacency. There is no need to fully engage with the work. The speed bumps wake us up. The act of sex itself is rarely an easy, smooth ride. A perfectly choreographed sexual experience, one without teeth clicking, a sudden cramp, a faux pas, or an awkward slip is memorable because of the surprise of its perfection. This is the exception rather than the rule. At least this is how it has always been in my own experience. These little glimpses of humanity are doorways for other people to enter the experience through. Most of us have clicked teeth in the heat of passion. When our characters click teeth we have a solid moment of connection with the work. We are transported into our past and we suddenly bring all the moments of complicated, imperfect sex to the table. Except, my friend Chris Somerville insists that when I write about sex I am never actually writing about sex. He says that I am always writing about loneliness, or lack of self-esteem, or the inability to connect with a person. In fact, he says, I am writing about the opposite of sex – about a lack of human contact concealed behind a wash of explicit language and graphic description. In the above example, he tells me that the scene is all about the moment when she picks up the phone and tells an invisible someone that she is not doing very much. This piece of writing he tells me, is not about sex, but about a lack of connection. Chris never writes about sex. He even finds it uncomfortable to talk about sex, and yet his work is infused with sexual tension. In his short story ‘Holiday’, he writes:

The possibility of a sexual encounter is always there simmering behind his words. I suppose this is what makes our work sexy, his work and mine. It is the surprise attack. In his work sex sneaks up on you when you least expect it. In my work sex is a smokescreen but there is something else behind it, thinly veiled. I have learned a lot from my conversations with my sex-avoiding friend. I have underlined the lessons I have learned but seem to always forget. I remember the power of subtext, of foreshadowing. I need to continually remember these lessons because I write about sex every day of my life in the blog that I have been maintaining for well over a year. I have struggled to find something sexy to say on a daily basis. I try not to repeat myself. Imagine having sex every day for two years and attempting not to repeat yourself. This is what it feels like on the days I drag myself to my blog, feeling decidedly unsexy. And so with the help of my writer friends and my heroes of the sexy story, Anais Nin and Georges Batailles, with the help of Raymond Carver and James Salter and Russel Banks and all the other writers whose work is sexy without actually talking about sex, I remember the most important lessons I have learned: Leave space, look for the unsaid, leave some of the work to your reader, and remember, whatever it is you are writing about, it is probably not what you are actually writing about. About the Author Krissy Kneen is the author of Affection: A Memoir of Love, Sex and Intimacy. You can read an interview with Krissy in an earlier issue of Perilous Adventures here.

|