| current issue |

| archives |

| submissions |

| about us |

| contact us |

| competition |

Kristina Ekman's The Dog reviewed Inga Simpson |

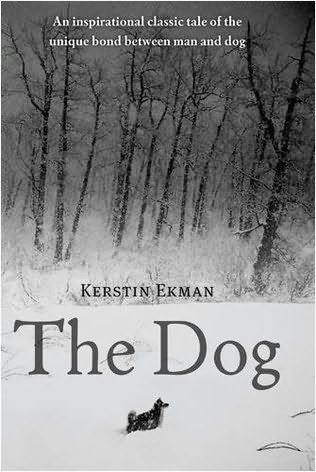

Originally published in Sweden in 1986, The Dog was published in English for the first time in 2009 by Sphere. Kerstin Ekman is one of Sweden’s most successful novelists. Her awards include the Great Prize for Fiction (1977), the August Prize (1993), the Nordic Council Prize (1994), and the Pilot Prize (1995) and the Ivor Lo Prize (2000). She notoriously stepped down from the Swedish Academy in 1989 because it failed to condemn the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. Born in 1933, Ekman emerged in the 1960s as a thriller writer before moving on to feminist and historical themes. Her crime novel, Blackwater (1993), published in English in 1996, received the Swedish Crime Academy's Award for best crime novel and became an international bestseller. Her other works are only now beginning to be translated into English. Ekman’s more recent fiction features magical realism and environmental concerns. Her latest work, Masters of the Forest (Herrararna I skogen, 2007), is a collection of essays about the forest. Like much of her fiction, The Dog is set in remote northern Sweden, near the Finnish border, where Ekman has lived for more than thirty years. It reflects her interest in wildness, wilderness and the relationship between people and nature. In the tradition of London’s Call of the Wild, The Dog is told from the dog’s point of view. Ekman has said: The dog’s perspective is the most appealing and effectively executed aspect of the book, particularly the pup’s early fear, the strangeness of the world he finds himself in: “The moon creeps up on the forest. The night is not silent” (30). Other animals are shapeless and strange, without names: “the one who swooped down” (83) or “a long tail, a vanishing streak” (22). Smell and sound and hunger are all-important. When it is windy all smells have “vanished from the world” (36). When the frozen lake thaws, the river roars and the wind whips up waves. For the dog, meltwater is “Hungerwater” (30). The reader holds their breath at times as the dog grows in confidence and strength, living through the change in seasons, learning, no longer afraid of shadows. He is injured but persists, matures into an adult dog, watchful, able to survive. There is a strong sense of animal consciousness, deep and instinctual: “Everything that happens is inside him. It has already happened … he forgets but knows” (85). The narrator’s environmental concerns, particularly regarding the strip-clearing that occurred in Sweden during the 1970s and 1980s, are addressed through the dog’s eyes. He runs from human activity on the lake and roams cleared hillsides, missing his forest:

The narrator’s voice intrudes here, naming things the dog could not know. The dog’s paws are cut by sharp rocks, rusty iron and broken beer bottles, he struggles to find food and water without the forest. Ekman’s deep knowledge of the forest and dogs is apparent in every sentence, and the writing, on the whole, is a pleasure. There are, at times, a few too many adverbs, and an occasional clumsiness of language that may well be a result of the translation. The Dog is subtle and uplifting, timeless despite the long wait to read it in English. *** The Dog by Kirstin Ekman |

“When does something begin?” The enduring cycle of nature is at the heart of Kerstin Ekman’s The Dog, the story of a domestic pup separated from his mother and forced to fend for himself in the winter forest. He survives, relying on his instincts and luck, transforming into a wild animal. Before the next winter he is found by his former owner and coaxed back into a degree of domesticity.

“When does something begin?” The enduring cycle of nature is at the heart of Kerstin Ekman’s The Dog, the story of a domestic pup separated from his mother and forced to fend for himself in the winter forest. He survives, relying on his instincts and luck, transforming into a wild animal. Before the next winter he is found by his former owner and coaxed back into a degree of domesticity.