| current issue |

| archives |

| submissions |

| about us |

| contact us |

| short story competition |

sponsored by

Charlotte Wood Interviewed by Sandra Hogan |

||||

|

Perilous Adventures interviewed Charlotte Wood in the studio which Eleanor Dark built in the 1930s among the garden beds of Varuna, so she could escape the housework and the ringing phone and concentrate on writing her novels. When Eleanor died, her son Mick gave the beautiful house, studio and all, to a foundation which allows writers to come and work among the clouds and trees and silence of the Blue Mountains. Charlotte Wood has been a regular guest there since 1996, and it has played a part in the writing of her novels Pieces of a Girl (1999) The Submerged Cathedral (2004) The Children (2007) and the collection of short stories she edited, called Brothers and Sisters (2009). In May this year, Charlotte came to Varuna, the day after she had completed editing work on her new novel Animal People, to start work on a non-fiction work about food. I met her collecting wood in the garden to build a fire, and mistook her for a gardener. She is comfortable in gardens and in kitchens and, although she lives opposite a large shopping centre in Sydney, she has the air of a capable country woman. As an old hand at Varuna, she made a point of welcoming and including other writers at the house and was generous in listening and talking about the craft of writing.

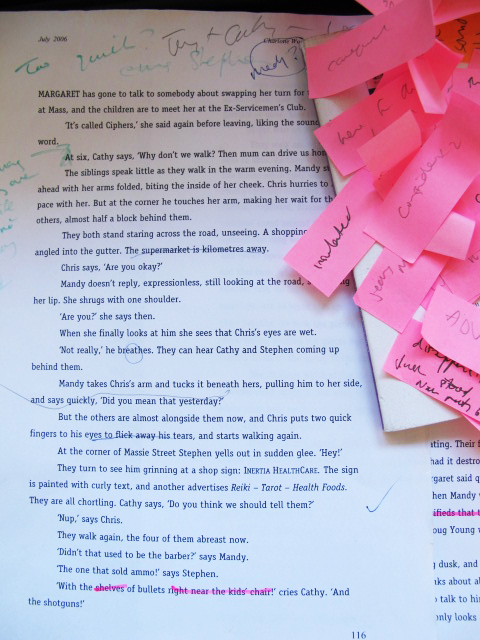

PA: Tell me what you’ve done today. I’ve been working on this non-fiction book about cooking. It’s more about the emotional terrain of cooking than the actual food, although it’s going to have some recipes as well. Some of it is about cooking at big moments of life. It started out as a practical, hands-on book about making food for people who are sick or bereaved or whatever, because I’ve done a bit of that and had it done for me often, and I think it’s a really nice thing to do - but it didn’t really have enough scope for a book. So while that stuff will be part of this one, it’s a broader book of mini-essays about the ways that food can connect us to other people in daily life, and the role of cooking and eating in my own life. I’m having a little struggle this week working out how to set the tone, and how to combine the meditative and the practical stuff so that’s why I’m looking a bit wild-eyed at the moment. PA: So as a writer, you’re terrified by each new project like all the rest of us? Of course. Absolutely. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t feel like that at the beginning. Years ago, after I’d written my first book, I didn’t feel like that. I thought, ‘Good, I know how to do it now’. Which, of course, was a great error. And I remember someone saying at that time, a much more experienced writer than me: ‘Well, you know how to write the book you’ve just written – you don’t know how to write the one you’re going to write.’ I think that’s really true. Especially if, as I think most writers do, you’re trying to extend yourself each time. You don’t want to write something you know you can do. You want to stretch yourself, just to keep yourself interested. PA: You’ve talked about how in The Children, your stretch was to conquer narrative drive. When you say you want to challenge yourself each time, do you actually set yourself a task? I set myself a technical task as well as perhaps a setting, or having the beginnings of a character. And later, in second or third draft, I have begun to uncover the themes - which then need lots of exploration.. With the first book, I just blundered along. I had no idea of what I was doing. In the second one, The Submerged Cathedral, I was interested in the form of the love story and how you could work within that without turning to schmaltz or sugar. I had this back story about my parents, whose meeting had quite an epic structure; it was love a story that in my family we all grew up with. I wanted to see what I could do with that story but make it my own. So the love story structure was my technical thing with that one. And for me each book is in some way a reaction to the previous one, which I think a lot of writers do. So with The Children, I wanted to write something much tougher and more contemporary. I wanted something set in a country town with grown-up siblings and I wanted to ramp things up in the plot department. So that was my challenge: how am I going to put these things together? Gradually the bits start to coalesce. PA: You’ve talked about your studies with Sue Woolfe and how you start writing with fragments, but can you outline how that works? I’ve moved away from that completely fragmentary process now. It worked really well for the first book when, like so many beginner writers, I thought, ‘I don’t have An Idea for A Novel, so I can’t write a book.’ That work with Sue was really important in helping me to realise that’s how many writers feel and how they begin to write. But since then, since I started getting this feel for finding myself a technical challenge or a setting to begin with each time, I don’t start with nothing anymore. I still write in bits and bobs, though, and for a long time I don’t know if they’re connected or not; a lot of them get chucked out. So in The Children, the process was that I had to find something that would bring the grown-up children back to their home in the country town, and to put them under some kind of pressure. I would have liked to have a bigger family but that’s hard to pull off without losing an intensity of focus, so I chose to go with three siblings. Three is such a potent number. It seems to have a symmetry but also has an asymmetry, an oddness – Michael Cunningham was speaking about this at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, how the introduction of a third element immediately creates some possibilities that you can’t have with two. So I could play one sibling off against the other two, and they could have shifting alliances and so on. So at the start I had little bits of each character. PA: Do you always start with characters? Yes, and with place. In some ways, I think place is just as important. PA: Why a country town? I grew up in a country town [Cooma]. I love Australian country towns, but I’m not romantic about them. Three of my siblings still live in different country towns. I think there was a lot of potential in that kind of setting to create a crucible for this family to be pushed into. It echoed with the siblings returning to childhood as well, pushing them back into the place where they had been adolescents together and pushing them back into that kind of adolescent behavior. I think if you grew up in a country town and you left it as an early adult, going back there has a very potent effect of pulling you back to that time. Growing up in a city doesn’t necessarily have the same feeling, because you might leave but there’s much more possibility that you’re always going back and forth. It’s not like really properly leaving. So I guess the setting needs to reflect the characterisation. They need to be important to each other. PA: It sounds like you work it out in quite a technical way … But I don’t think I know all that at the time. PA: So you just start writing … So you start writing and themes emerge and characters emerge, but with that book I had about 50,000 words and then I thought, ‘I’d better have a look at this and see what I’ve got now.’ I spend quite a long time trying to find out who the characters are before I start trying to construct some sort of narrative or focus. And with that book, because there were so many characters, I realised after about 50,000 words I had to work out who was my main character. Am I going to have the total ensemble, which is harder to sustain as the beginner writer that I still feel I am, harder to manage the reader’s allegiances, I suppose. So I got out my 50,000 words and I realised Mandy was my main character. She was the one I was most interested in. So then I knew I had to get rid of anything that didn’t have to do with her, or stuff about the other characters that didn’t illuminate her in some way. It could be stuff about their childhood, for example, but it had to have some thread back to Mandy. And so that day I threw out 30,000 words. PA: Wow, how did that feel? It felt terrible. But what it did do, and what made me feel better really quickly, was that it revealed the story to me, the bones. So then, instead of it all just being a big swamp, the writing suddenly had some shape and I could start to see, OK now what do I need? Otherwise it would have been too opaque and I wouldn’t have been able to see what I needed. So after that I was like, right, something’s got to happen to her and she’s got to be the driver of everything and she’s the one who has to be revealed to herself. This thing of writing in fragments involves a lot of anxiety and grief when you have to chuck it all out. But another friend of mine, Tegan Bennett-Daylight, has talked about the first draft as being like scaffolding around the building. At some point you have to take away that scaffolding to really see what you’ve got. So it doesn’t really bother me anymore. With this novel, the new one … PA: Yeah, tell me about the new one now The new one is called Animal People and the main character is Stephen from The Children, so it’s kind of a companion book. It’s not really a sequel, because the others aren’t in it - although Cathy, the younger sister, does appear on the phone and the mother has a cameo phone appearance too. But Mandy’s overseas, gone. PA: Ah, so she’s back doing that! Yes, she’s back doing that. Her husband Chris is very involved in this story, though, because he’s remarried. PA: Goodness. Well it was probably wise, really. Yes, it wasn’t going to work. PA: No, it wasn’t ever going to work. I had a couple of technical issues with this one. I don’t know why I decided this, but I decided really early on, it was one of the first things I decided, was that it was all going to be set in one day. It’s going to be Stephen going from one side of the city to the other and back again. I started out wanting - this is going to sound odd, but I wanted to write a romantic comedy. Again it was a kind of reaction to the last one. I found it very hard to write that last one and I thought, I want to have some fun. PA: Hard emotionally? Yes, well I don’t want to sound too extravagant about it, but for me there was a lot of thinking about moral issues, about what it means to witness the suffering of strangers, on the television news and so on, and what our moral obligations are in relation to that. As it turns out, this new book ended up entering into that question in a different area, but at first I wanted to do something light. I also wanted to try writing something funny, because I’d never really risked doing comic writing before and I think I found I had begun to default to a tragic position. To get some sort of gravitas, it was becoming too easy to kill someone, or write in some sort of tragic event It could easily become a kind of tic. I don’t think that was the case in The Children, but if I had done it again it could have been. So my starting point with this was one day, pluscomedy, plus a a kind of love story. But having done a country town, this time I also wanted it to be completely urban. PA: So not a crucible this time? No. Or not in the same way. Last time the country town, and the family home, worked as what film-makers call the single arena, where you’re trapping people together PA: … in a lift or a boat? Exactly. This time I’m hoping the city will act as my arena here. I want to really write a portrait of city living. Again this is in retrospect that I can see what I was doing. PA: Is the city Sydney? It’s not named as Sydney. I would like it to be any large city, although people who read it have immediately identified it as Sydney, so it’s probably like Michelle de Kretser’s book The Lost Dog - that book is so Melbourne that it couldn’t be anywhere else, even though Michelle didn’t necessarily want it that way. But for a start it’s got trams, and it’s in Australia. And mine’s got a harbour, so it’s hard to avoid readers thinking of Sydney. But I’m hoping that, apart from this, the urban landscape could equally be another city in Australia. PA: And you did the same thing this time of starting to write and write until you could see what it was? Yes, but in some ways, the shape of this came to me really quickly, almost in one go, which was the opposite of that fragmented thing. I had my crucible with the one-day timeframe, because everything had to happen within 16 hours. I knew fairly quickly that when Stephen gets up in the morning he knows that, at the end of the day, he’s going to dump his girlfriend. Hopefully the reader doesn’t want him to do this, so that’s where the tension is: ‘Don’t do it, you idiot.’ And he is an idiot, though I sympathise deeply with him. But as he moves through the day, things start to go wrong as soon as he leaves the house. He works at the zoo as a sandwich hand in a fast food kiosk, and he knows he has two ghastly things waiting for him at work – first he has to clean out the deep fryer, but then he has to go to the excruciating annual motivating team-building exercise. PA: Oh, it is a bad day. Another thing that’s waiting for him is that Fiona, his girlfriend, has two little girls whom he loves, and it’s one of the little girls’ birthday party. So he knows he has to get through this shitty day at work, and then go to Fiona’s, endure the birthday party, where Fiona’s parents are going to be present. This is going to sound very complicated but Fiona’s brother is Chris from the last book (Mandy’s ex-husband). Stephen feels very oppressed by everything in his life and one of the things that oppresses him is this knotty relationship, that he’s going out with his ex- brother-in-law’s sister. And he feels that this is all too much for him even though they’ve always had the hots for each other, since they first met well over a decade before. And Fiona’s great. She’s really the only good thing in his life. So you can see straightaway, hopefully, that if he’s going to dump Fiona, he’s going to end up in a bad way. He’s got this opportunity to really connect, and to build a beautiful thing with this woman and her kids. But although he loves them, because he is still rather immature and doesn’t think clearly, he’s operating on a kind of blind instinct which simply tells him that he just wants ‘to be free’. And he doesn’t even really consider or understand what that might mean. So at the start of the book he knows he’s got to these unpleasant tasks to deal with but on the way there, various things happen. He has an accident in his car. He has a few confrontations with various people that cause him more and more stress. The day’s one of those stinking hot summer days where it just gets hotter and hotter. So the pressure rises through because of all these things, but hopefully also emotionally the tension is building for the reader. When he gets to the party, things go even worse than he expected. Fiona’s ex-husband, who he hates, is there. Things go very badly wrong and … he’s sort of faced with what he’s done by the end of the day and it’s not good. But there is a chance, despite everything, of a happy ending. The theme of this book is our relationships with animals. Stephen is violently allergic to animal hair, as I am. And he works at the zoo, but he’s completely bewildered by people who describe themselves as ‘animal people’. You know, ‘I’m a dog person’, ‘I’m a cat person’. ‘I love animals’. He just doesn’t get it, but he knows it’s him who is weird, that he’s the one lacking in some way. A lot of it’s about the way we anthropomorphise animals, especially those of us living in urban society, which I find quite bizarre, the personification of animals to a degree that is ridiculous. In the suburb near me, in Newtown, there are shops which sell clothes for pets. I find this kind of thing to be deeply disrespectful to the animal, this kind of foolish nonsense, which is also about consumption, but it’s done by the sorts of people who believe they love their pet, which they then stuff into an Elvis suit or whatever. And it’s a very urban phenomenon. I don’t think you’d find that kind of thing in the town where I grew up, where there are farmers all around. I don’t think anyone there would think about animals with any of that level of denial. And so, all through the story of Stephen’s day, there’s this sort of skittering of animals all around him. Sometimes Stephen is aware of them and sometimes he’s not. He’s fearful of animals but what we come to understand, as we go through the book, is that his fear of animals is a fear of life - and in the end, he has to be pushed right up against that fear, literally, with an animal, to understand what he’s been doing all this time. And the question is, does his understanding come too late? Or is it not? There’s so much potential at the zoo for mad stuff with animals. I spent quite a bit of time at zoos writing this. Human behaviour at zoos is very strange. PA: How does research fit into your writing? You seem to do a lot. That’s interesting. I feel like I don’t do any. I read a lot. Sometimes, if it’s a concrete thing I do, like in The Children there’s a scene about kite flying. Sean and I made one. My father used to make beautiful kites when I was a child. Sean and I made a couple of kites which were a complete disaster but that helped with the scene. You think a kite is this beautiful thing, and you put it up in the air and it flies. But most of the time it doesn’t. It clomps to the ground. Or, in our case, a dog came and tore ours to pieces. PA: With The Submerged Cathedral, the scenes in the monastery … I did a lot of travelling to look at monasteries and a lot of reading. One thing I do a lot is look at images. At all the zoos I’ve been to, I’ve taken photos, and watched people. In some way, the city is a human zoo in Animal People. You realise that people are so captive to their situations, their jobs, the way they’re trapped into their relationships with each other. When I first thought about the zoo, I thought, ‘good, that will be funny’. An old boyfriend of mine used to work at the zoo as a sandwich hand and people used to say, ‘Where do you work?’ He’d say at the zoo and they’d say ‘Oh wow!’ And then they’d hear that he was just putting chips in a fryer and it didn’t have quite the same gloss. So I thought it was quite funny and I also thought it was a good place for family meltdown scenes. Plenty of those go on at zoos, I’ve noticed. But then later on a friend of mine, who’s a psychotherapist, asked me what I was writing. I told him a bit of it was set at a zoo and he asked why. And I started to wonder why it was at a deeper level, and to think about the potential of it. It raises all kinds of questions about captivity and freedom and why we want to go to zoos and what do we get from loving animals - supposedly - but locking them up in ways that quite often are just horrible. But also it led to me examining this cutesifying of everything that goes on. You might be aware of the baby elephant that was born at Sydney’s zoo last year or the year before and the amount of nauseating sugary media coverage it got. It makes you want to throw up. This sort of, we have to pretend it’s like a human baby. I don’t think it’s necessarily particularly harmful in itself, but it seems to me a massive kind of denial of the animal’s animality, its very essential nature is denied in order to make it lovable. But the zoos do it themselves; I suppose it helps them raise money for conservation and research and whatever. But it seems so depressing to me that we have to do it like that. Will no one give any money to the zoos if we don’t give the mother tigers wrapped-up presents on Mother’s Day, which I saw on the internet the other day? I don’t know why it depresses me so much, but it does. But also, during the process, I was given a great book by John Berger called Why Look At Animals? and part of that’s about zoos and I started reading theoretical stuff about zoos and cultural studies essays about zoos, and all that was really interesting, about the way people behave in zoos. It’s kind of like shopping. There’s an acquisitive vibe to it in many ways, I’ve seen it when I’ve been hanging round in zoos. Especially when people are taking photographs. People saying, ‘Did you get that one? You’ve got to get that one and then go get that other one!’ It’s completely unconscious, of course. It’s sort of like you’ve got to get your money’s worth - and then you go to the shop and you buy a whole lot of landfill, which is destroying habitats all over the planet, in the guise of conservation. It’s so mixed up and weird. I don’t really have any messages about this, other than pointing out how how much denial we’re in about our relationships with animals, but at the same time, I know I have some of Stephen’s fear of life – of unpredictability and unruliness - and of the way his aversion to domestic animals says something about him. In some ways anthropomorphism has a positive role in that it promotes empathy with animals that 20 years ago … hopefully we’re slowly improving farming practices and that kind of stuff but I don’t know if that will ever really change. PA: So you started with a little romantic comedy and … Yes and now I’ve ended up with this whole ethical minefield of human/animal relationships. PA: You know you said Stephen doesn’t think clearly. I’m getting the sense that you’re a person who does. No! No, I’m not! I’m a deeply confused individual. In some ways, what keeps me writing is that the books are an attempt to work out a problem, an ethical or intellectual problem. Doesn’t mean I do work it out but, years ago, I read Peter Carey saying ‘I write to find out what I think about the world’ and that really rings true for me. That’s the only thing, apart from the artistic challenges of making something beautiful and telling the truth as much as you can, that thing of nutting out what I think, that is really interesting and satisfying, even if you don’t work out the answer. It only really started with The Children, although with The Submerged Cathedral I had a problem about where does one’s duty lie – your duty to yourself compared with your duty to other people – but if I was writing that book now I would really get into that idea much more explicitly. PA: Yes, I didn’t quite see why she did so much for her sister … Yes, a lot of people saw it like that. For me it was a perfectly truthful instinct, that she was bound to do her duty by her sister. And I think now I would think the character can still behave with that instinct but the writer needs to be more aware of what it means. Now I would explore that much more comprehensively. But the thing with Stephen in the writing process, which has been a big fat pain in the arse, is that he’s kind of oblivious and yet the whole book is from his point of view. PA: Wow, that’s hard. Yeah, but you don’t really know when you start out what problems are going to arise. I would know now for next time: don’t do that. But that’s part of the jigsaw, making it work. While he’s an unreliable narrator, in some ways hopefully the reader can see things that he can’t see. Cathy comes in as a voice of reason in this book. She talks to him on the phone and figures out from the way he’s talking that he’s going to break up with Fiona. So she’s my clear-eyed voice saying, I see what you’re doing and don’t do it, you idiot. She says ‘I’ve worked out why you like working at the zoo, because you like your life forms behind glass and behind bars, so you don’t have to get in there and wrangle with life. You can keep it at a distance and just walk away.’ And he says, ‘What a load of bullshit, you’re an idiot’, and hangs up. But hopefully the reader is quite aware of what he is. And it’s tricky, because you can overplay that, or be too heavy-handed with it. It remains to be seen whether it works.

PA: But you’ve finished it! And yesterday you finished the copy editing. Yes and I got an email from my publisher this morning saying it all looks good to her. PA: Who is your publisher? Jane Palfreyman again. Thank God. PA: And now you’re working on the next book. Yes, well there’s this kind of crossover lag thing because I finished the book enough to go to my agent last July. Then she had some really good comments about how to improve it so I rewrote it and sent it back in August. They made an offer in September. I didn’t start editing until February. So that’s quite a long time to do nothing., so that’s when I started on this food book. But I tend to find, and I’m quite glad it’s worked out this way, that I often get to a point in the book where I think it’s not working, I can’t do it, and I hate it and I don’t want to do it anymore. And then I’ll have an idea for a new book, at least a glimmering of an idea. And that really happened when I was sort of in the middle of this Stephen book: I had this fantastic idea for a whole new novel, and I thought ‘I don’t care about this stupid one anymore, I’ll just finish it and get it out of the way and get on to the one that’s really going to work’. And that somehow frees me up and alleviates the anxiety – this kind of feeling of having all your eggs in this basket but it’s a crap basket and the eggs are in danger - and then I was able interested in the Stephen book again. PA: How long did it take you to write Animal People? In the middle of writing it I stopped and edited the Brothers and Sisters collection. I took about a year off the novel to do that and I thought the novel had died of neglect. In retrospect, I think it was good because it was only after that that I got this animal stuff happening. It was almost like I had to find something new to revive my own interest in it. If it didn’t have that it would be just a rather thin love story with no thematic interest. Although the animal theme might have developed anyway or it might have not. So I would say it took three years in actual writing time. In the middle, we were renovating our house and living in about 10 different houses and it was good to have a project like the anthology to do which didn’t need me to be really quiet and focused. There was commissioning the other stories and writing my story, but I didn’t need a whole year to do that. PA: How does life fit in with your writing? Do you have a job? I have a job that is incredibly accommodating of my writing life in that I commission and edit articles for a monthly medical magazine and I mainly work at home. PA: Tell me about your daily writing routines. I have, very luckily, a separate studio from our house, so I work there. And it goes through phases of productivity. There are some weeks when nothing happens because I’m completely working at my job or just doing stuff that life demands or doing a bit of journalism or a bit of website work. But when I’m in the writing mode, I will usually do at least three or four days a week of solid writing. I try to do 1000 words a day. Sometimes more. And often less. But I pretty much tend to stick to about 1000 words a day if I’m in that zone. I might get that done in two hours or I might press the word count button obsessively every 10 minutes. At 1000 words, I’m allowed to stop but sometimes I do more if I’m on a roll. That’s how I work for the first draft. I try to be at the desk by 8.30am. PA: Any little rituals? Only procrastination, like reading through my email. The first draft is very messy. I don’t look at stuff from the day before. It’s just words on a page. It’s all about quantity at that point. I push through until I get to about 30,000 words or more, until I feel that I can’t go on any more because I’ll just bore myself to death, or I feel like I need to step back and look at what’s come up – what are the themes that have begun to rise up out of it. And at that time I might take a couple of weeks away at a friend’s house or wherever, where I can be by myself and just work. With the Stephen book I did one of those 10,000 word writing days very earlyon. It was quite exciting. I’m a slow writer and I feel like I write in such dribs and drabs and I thought, oh fuck it, I’ll just do it. That way, maybe I’ll get 2,000 usable words instead of just one. It helped for that stage of fleshing out the characters, and putting them in ten different situations. I’m sure I didn’t use a tenth of it but it did seem helpful to me even just from a morale point of view. You know, well I’ve got 10,000 words and I might not use them but it’s taken me a day instead of six months to get 10,000 words I won’t use. PA: Do you consciously try your characters out in different situations? Like, what would happen if the deep fryer broke down? Yes. I thought, what could happen in a day? I know he’s got to go from here to here. Where are the places that he goes? Who are the people that he might cross paths with? How can he be put under pressure in every step of the way? Just like when you yourself have a bad day. You think, well, what happened to make it such a bad day? Things unexpected happened. So with Stephen, for example, he runs into a pedestrian in his car. That was something I’d seen happen near our house and I was appalled because we stopped, but we were the only ones. The person that hit her didn’t stop. Cars were just whizzing by. It’s not a very nice portrait of city life this book. I think part of it is playing out my own frustrations of living in a big city and the inhumanity that happens around you on a daily basis. PA: Do you keep a diary? I keep a notebook. Or I write stuff on my phone when I get on a bus or see people in a shop. Much more in that first draft stage. I wish I was always doing it. Though maybe I do always do it. I see things and think, ‘oh, that might work’. Or Sean, my husband, will tell me something he saw that day that might be useful to me. For this book I was always looking for funny things or absurd things or poignant things. PA: So you’re watching people and taking photos. Yes I take photos of places and put them on the walls around me while I’m writing. Because it’s really easy, especially with something like a zoo, to have a mental picture that cuts out a lot of what’s actually there. When you have photographs, you see that there are three garbage bins and a woman with a tattoo and a forklift and then the monkey house. It’s not just the monkeys in the trees. There’s all this human detritus all around which helps anchor it in the reality that I wanted. For this book I wanted a really urban realist kind of atmosphere. And those pictures help you look properly at this stuff about humans and animals. So for example there might be a bit of fake nature that they put around the animal, some pebbles and reeds and whatnot, but then no more than a metre beyond that is all this human garbage. Every now and then I make an attempt to organise my notebook observations which is always haphazard. PA: To type them up? Sometimes I put files on my computer of, say, ‘people’ or ‘streets’. I have piles of notebooks of stuff that I occasionally look at but often don’t. But somehow it seems to go in anyway. PA: So it’s more the writing of the note that’s important, than the actual note? Yes. PA: Do you have favourite pens or pencils? No. I have a friend who will only write in one of those yellow Spirex notebooks and with a certain type of pen but I’m much more … PA: And you keep a messy office? Yes, I keep a messy office. It’s been remarked upon. PA: And do you read while you’re writing? Yes. I don’t understand people who don’t. I find I need it. It’s like air. I love reading stuff that’s quite different in style. It’s as though I can get an injection of a different tone or a different language or you can see plot things and you go ‘Ooh’. I’m learning all the time I’m reading. Even if it’s something I don’t like, I think ‘What’s wrong with this? Am I in danger of doing this?’ I also have dinner every couple of weeks with this bunch of writing friends. We’ve been doing that– we used to do it once a week – for about 15 years. From before my first book. It was the year after my mother died, that was 95. And that’s great. PA: You read out of your work to each other? No, not so much. We often write, do little exercises. Some of us met in writing classes. So we’ll often have a little extract from something we’re reading, a paragraph or whatever and do one of those improvisation 10-minute writing exercises. And we’ll always go around and talk about what we have been doing. I’ll say, ‘I’m so sick of it I can’t stand it anymore’. They’ll say, ‘Have you tried this? Have you tried that?’ We started with really the simple aim of just helping each other keep going. So it wasn’t about critiquing the work or anything but saying ‘Let’s keep going’. Now they are my first readers. There are four of them and they’ve all got completely different brains from me and from each other so each one will pick up completely different … I mean they will almost always all identify a big problem and that’s very handy because you know, Oh I thought I was getting away with that but it’s clear now I’m not. Or one person will say, ‘This bit is not working’ but if two of the others say, ‘I liked it’, then it’s my own decision. But if everyone says the beginning’s too slow, or whatever, I would listen. PA: You like to get fairly robust criticism? Yeah yeah! But from them it’s never too traumatic. I think we’ve all upset each other from time to time but it’s serving the work, not the person. We’re very lucky, somehow there’s no ego or competition or whatever involved. I don’t know how that’s happened but it is the case. And the more experienced we are, the better we are at either saying ‘Keep going, it’s not my bag but I can see what you’re doing’. But we’re also better at resisting advice when we know it’s not right for us. PA: And do you have a mentor or a teacher? No, they are my buddies, although my agent was really fantastic with this book. PA: Who is your agent? Jenny Darling, in Melbourne. With The Children, I must have been further along with it when I sent her the book. Because she said, ‘Yes, I think it’s ready to go to the publisher’. And this time I expected her to do that, but she said, ‘I don’t think it’s ready’. And I thought ‘Oh shit’. But it was great. She was very helpful. And I felt empowered to go back and rework it. And then Jane, my publisher, has been a huge huge supporter and Judith Lukin-Amundsen has been my editor again and she’s wonderful. So I feel like we’ve got this really nice team now who take care of my book. PA: How does marriage work, in terms of your writing? Pretty easily for us. We don’t have kids. PA: Was that a decision because of your art? No, I just always knew that I wouldn’t. When I was a kid, I thought ‘that’s not for me’. I love kids. I love other people’s kids. We have 20 nephews and nieces who we try to spend a lot of time with but it’s worked well for us not having our own. I see my friends who are writing with children and having to earn a living and I don’t know how they do it and I can see the struggle to get the time is enormous. But at the same time I know other people who don’t have kids but who are working full-time in really demanding jobs and I don’t know how they do it either. For the last while I’ve been incredibly lucky to have a job that’s flexible and Sean, my husband, is really supportive. PA: Does he read your books? Yes, yes. When we were first going out I asked him to read a draft of my first novel which was a complete disaster. And I feel terrible now for even asking him back then because he didn’t know what to make of it and we really hardly knew each other. I don’t know why I did that. He was nonplussed by it and I was traumatised. So since then I’ve been much more sensible, so I give it to him at the last draft stage. And I talk to him about it all the way through and he knows what I’m doing. PA: And he’s interested in the process? Yes. He’s a creative person. He’s been a musician. And he has an art transport business so he spends all day with paintings and artists, who he loves. He’s got a really good understanding of the way creative people work and he works like that himself when he is playing music. I don’t think if we were both writers it would be a really good thing. He’s a really good reader. Just the other day I asked him to read a new little bit that I’d inserted into the copy. I really just wanted him to say ‘That’s fantastic’. And he said, ‘I don’t know about that last line.’ Shit. And he was right. So this time I’m going to ask him to read the proofs as well. He’s already read the second or third draft. But I’ll get him to read the proofs as well so he can pick out any of those false notes. He’s very good at that, where I’ve been trying to get away with something that’s not going to work. He’s invaluable to me as a reader as well as a very good person in my life. PA: Does being an editor help or hinder? I think it probably helps in that my copy is pretty clean. I try not to leave sloppy messes for editors to clean up. My punctuation is fine and my spelling is fine. So they don’t have to waste time on that kind of stuff. They can look more at the logic and wonkiness of expression. What I really like from an editor is for them to allow me to to take risks, like with a made-up word, say –that they have the sensitivity to allow that to a certain extent but they can be tough and pull me back when necessary. Not that I’ve done anything linguistically exciting with this one. PA: You seem to have been more linguistically adventurous in earlier novels. I think I’d like to get back to that a bit more in future novels. It’s all come from setting for me. With this contemporary stuff, I wanted to write a realist contemporary book, but with The Submerged Cathedral it was out-of-time. That book is in a bubble. I wanted it to be like that. I wanted it to have a lyrical quality. But that wouldn’t have worked for the subject matter of The Children and of Animal People. But I think with the next one it might be different. Who knows? PA: You’ve got an idea of the next one? Yes I’ve got a highly formed idea of the next one which I won’t say anything about because it will probably just make it fizzle in my head. PA: How do you feel about critics? I don’t write for critics. There are very few reviewers here, maybe a handful, who you could really learn something from as a writer, who have a real sensitivity and insight. I’ve had two really good reviews that have been among my most critical but also the most useful. I’ve respected what they said and I’ve learned from it. Most reviewing isn’t like that. A lot of them are just plot précis. But reviewing is so badly paid, who would want to do it? PA: And it’s awkward because it’s a small writing community and writers have to review each other. Yes. I wrote a couple of reviews when I started and I realised immediately it was a really bad idea for me. I wasn’t very good at articulating what I didn’t like and I knew what it felt like to get a bad review and I didn’t want to do it to someone else. I know that’s gutless but I think that if you’re a fiction writer it’s not your obligation to review. PA: One of the things you said in an interview that inspired me was about writing being a way of entering into a moment that you could easily pass over in life, a moment that holds a lot of meaning if you just sit and observe it. You talked about attention in almost a meditative way. Yes, I think that’s what writing’s for. For me anyway. I want to capture the moments that just pass you by in life. As a reader I want somebody to capture them. PA: Another helpful thing you said was that when you read something powerful it comes from the writer exploring as they write. The energy in good writing comes from that risk. I really think that. That sense of discovery, of not knowing what it is you’re doing, there is a sense of energy that comes from that. And if I’m writing and I think, ‘Oh yeah, I know how to do that, just put that there and move this here’ – it goes dead on the page. PA: The sibling stuff. It keeps coming up in your writing. What is that about? I don’t know. My poor siblings. People think there’s some issue in our family but it’s not the case. I just find they are so important to me. In some ways I wonder if it’s because our parents died relatively young that maybe I’ve focused on it more. Our parents both died when they were in their 50s, with a ten year gap apart. I was 29 when Mum died and 19 when my father died. I know at my brother-in-laws 40th birthday party recently, his wife gave a speech and she quoted some research she’d seen which showed your siblings are as important as your parents in shaping who you are. And then she very nicely said he was lucky he had such nice siblings. But I do think your siblings are a kind of mirror. They’re the person you could have been with some genetic tweaking. Also maybe my attention to siblings comes from the fact that I don’t have children of my own. I’ve only just thought of that this second. That’s why siblings would be the mirror, not my own children. Sometimes I think that if I did have a child I would be absolutely terrified. I would be faced with myself in a way I would not like to see. Maybe if I had a child I’d be less focused on that aspect of siblinghood. But also, my husband is from a big family, I’m from a big family. I love hearing about other people’s siblings. I don’t think that I’m writing about my own siblings. And certainly none of my sibling relationships are recognisable in The Children. I mean there’s an incident from childhood here and there but I don’t have those relationships with my siblings that Stephen and Cathy and Mandy do or that the two old ladies in that story in Brothers and Sisters do. PA: That story is so potent. One of the strong emotions I had when I read that was embarrassment. I felt like you’d caught me out. It seemed very deeply true to me. I’m so glad to know that. I wondered with that story. I went to Greece for my cousin’s wedding and my aunt came, my cousin’s mother, and she was in her 70s. I started wondering about, if my mother was alive, what would they be like with each other. And I don’t think they’d be like those two – for a start they were English, and very close to each other, and different kinds of people from my characters and they both come from families with seven kids. But as families get older and die off, it’s very poignant to me. I was wondering what it would be like if the one sibling you never had anything in common with was the one left with you at the end of your life; if the ones who were supposedly close to you were gone, and how would you realign yourself with that sibling… But you know, I think I’m kind of done with siblings. PA: Done that? With the fact that your parents died young, and it was cancer in both cases wasn’t it? Yeah. PA: I can see the reflection of that in Pieces of a Girl but, apart from that, is it also in the foreign correspondent stuff in The Children? Is that the origin of your sense of horror lurking underneath and around and how thin the walls are between safety and tragedy? Yes, that’s a really good way of putting it. I do feel that no matter how much you think everything’s all right, at any moment everything could be destroyed. My parents and some of my close friends have had cancer. One day everything’s fine, normal, and the next day your life is in danger. I think that happening with my dad, when I was 19, put a big hole in my sense of safety. I had always thought the world was a good and safe place and I think with Dad’s death, that belief was pulled out from underneath me. And then when Mum got sick, I felt, ‘whoa hang on, we’ve already had ours, that’s not supposed to happen’. You see it first as an aberration and then, when it happens again, you think, ‘Oh no, it’s not an aberration. That’s actually the way the world is.’ And after a while you recover from that extreme position but it never goes away. I’m an anxious, anxious person. I probably always was an anxious person but those things are formative for anybody and I didn’t really start writing until after my parents had died. And I don’t know if I would have begun if they hadn’t. PA: What does writing do for you? Is it like therapy? I hate the idea of writing as simple therapy because it negates that there;’s any art involved. But that said, for me it certainly can be about making sense of things and giving a shape to things. Helen Garner talks about that really clearly – that she needs it to shape her experiences into something she can understand. I hope that I would have become a writer anyway. I was always an obsessive reader and I loved English at school and my parents were creative people and my siblings have a lot of talent – one has been a milliner making beautiful hats, and another one teaches art, is a visual artist. So it’s a kind of a family thing – making things is ingrained in all of us in different ways. My mother was a beautiful gardener and florist and my father was really talented in all kinds of ways. And in a way, having children stopped him from practising an art, not that he would ever have thought of it that way. But he had quite serious talent, I think, as a visual artist – he made half our furniture, made props and costumes for the local theatre group, that kidn of thing. He was one of those dads who make everything, and fixed our electrical stuff, and built brick garden walls, and so on. So genetically we all got quite a big dose of creativity and were really encouraged in that direction as children. PA: Is there something freeing in the death of parents? There might be some things you’d be afraid of writing when your parents were alive? There’s a lot in that. Maybe I would have become a writer but maybe I would have found it harder. I can’t imagine writing sex scenes if my parents were alive. But it’s a bit facile to say that, and in fact if I ever think of anyone I know reading what I’m writing at the time I do it, I want to die of embarrassment, not just the sex scenes. I suppose in some ways I feel if my parents had lived longer I might not have the experience of grief and survival, and the big questions of love and death and how to go on would not have occurred to me yet, because I wouldn’t have had to face them. I might have gotten too happy too early to find anything complicated enough to want to spend years excavating. Sometimes I can’t believe I go on about this so much, when half the people I know have lost their parents, or had much more awful things happen to them. But I guess it’s just my thing. I remember Elizabeth Jolley quoting Flaubert: ‘Fiction is the response to a deep and always hidden wound’, and I suppose if there’s any wound that has been a sort of portal into a creative life for me, a wound that pushes one to transpose life into art, then this is mine. More Author Interviews Gary Crew interviewed by n a bourke (Issue 09:03) Patrick Holland interviewed by n a bourke (Issue 10:03) Belinda Jeffrey interviewed by Inga Simpson (10:02) Susan Johnson interviewed by Sandra Hogan (Issue 11:01) Krissy Kneen interviewed by n a bourke (Issue 09:05) Steven Lang interviewed by n a bourke (issue 09:04) Pippa Masson interviewed by Janene Carey (10:02) Lisa Unger interviewed by Inga Simpson (10:01)

About The Interviewer

|

Sandra Hogan has worked as a shop assistant, supermarket shelf stacker, public servant and journalist and she now supports her writing habit by teaching business people to write reports and letters. She is fascinated, among other things, by the science/religion wars. She is working on a book of linked short stories about lost things. She is the director of

Sandra Hogan has worked as a shop assistant, supermarket shelf stacker, public servant and journalist and she now supports her writing habit by teaching business people to write reports and letters. She is fascinated, among other things, by the science/religion wars. She is working on a book of linked short stories about lost things. She is the director of